Depersonalisation and derealisation: assessment and management

BMJ 2017; 356 doi: https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.j745 (Published 23 March 2017) Cite this as: BMJ 2017;356:j745

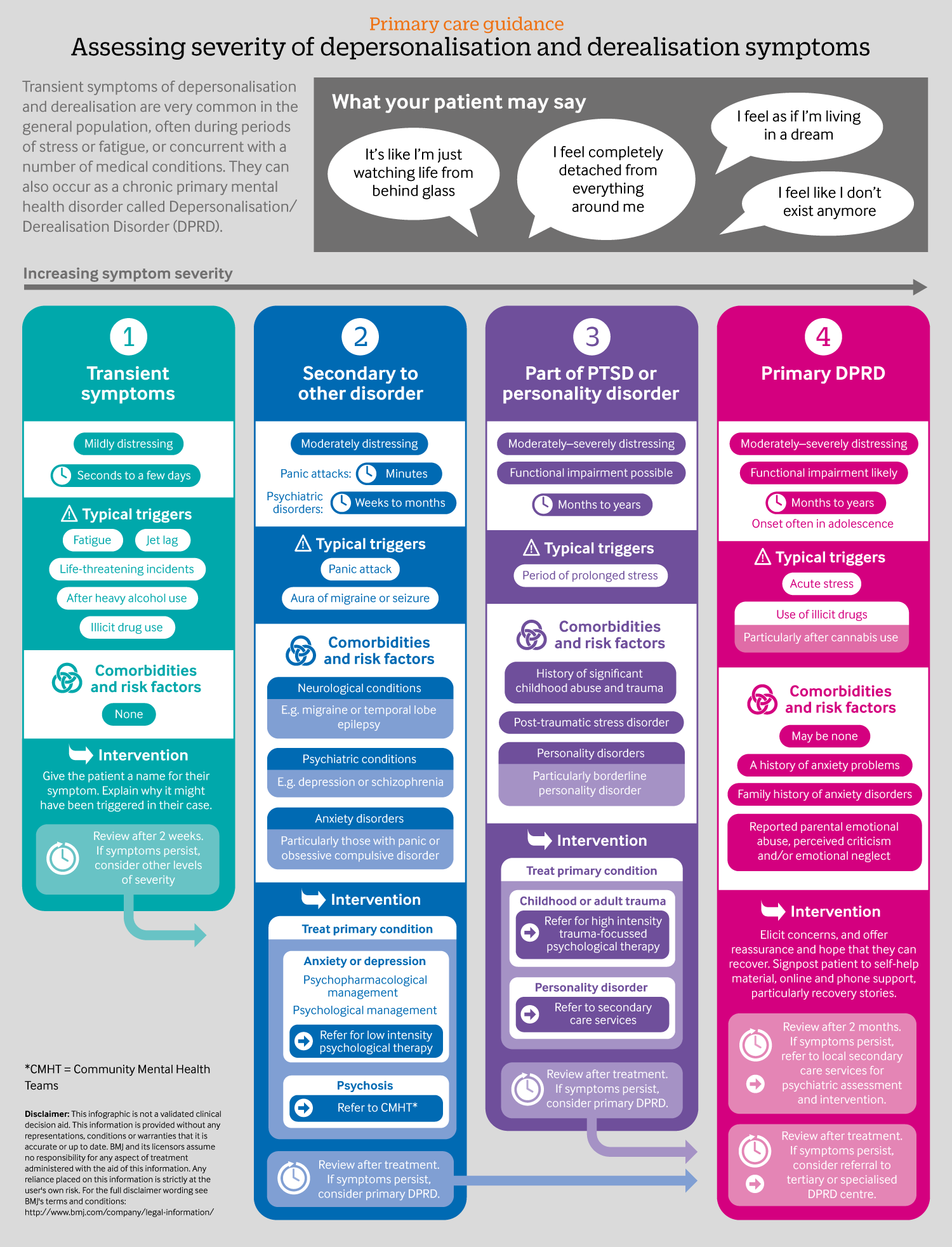

Infographic available

Click here for a visual summary of DPRD symptoms and severity, including common triggers, comorbitities, risk factors, and suggested interventions

- Elaine C M Hunter, consultant clinical psychologist1,

- Jane Charlton, patient who has experienced depersonalisation/derealisation disorder for seven years2,

- Anthony S David, professor of cognitive neuropsychiatry3

- 1Depersonalisation Disorder Service, Maudsley Hospital, London, UK

- 2Rethink Mental Illness, London, UK

- 3Institute of Psychiatry, Psychology and Neuroscience, London, UK

- Correspondence to Elaine.hunter{at}slam.nhs.uk

What you need to know

- Depersonalisation and derealisation symptoms include having a sense of unreality and detachment; patients may describe using phrases such as “it is as if . . . ”

Symptoms are often triggered by adverse life events, severe anxiety, or cannabis use

Transient symptoms of less than a couple of weeks’ duration are common and need no intervention

Distinguish symptoms of depersonalisation and derealisation that are secondary to another medical or psychiatric diagnosis and treat the underlying problem

Refer those who appear to have persistent symptoms to a psychiatrist for consideration of primary depersonalisation derealisation disorder

Patients who experience depersonalisation and derealisation often have difficulty in describing their symptoms. They experience a sense of unreality and detachment from their sense of themselves (depersonalisation: DP) or their perception of the world (derealisation: DR). In most cases these two symptoms co-occur. This article aims to help clinicians recognise depersonalisation and derealisation (DP DR) symptoms, diagnose the disorder, and discuss current treatment options.

Who experiences depersonalisation and derealisation?

Otherwise healthy people—Transient symptoms of depersonalisation and derealisation are very common in the general population, often during periods of stress or fatigue. One US phone study of more than 1000 people found that nearly a quarter reported a brief episode over the previous one year period.1

Those with a range of physical and mental health conditions—Such symptoms are also commonly associated with several medical conditions, such as migraine and temporal lobe epilepsy,2 and with psychiatric conditions, particularly anxiety disorders, such as panic, depression, or in those with complex post-traumatic stress or personality disorders who report a history of childhood abuse or trauma.3

Those with depersonalisation and derealisation disorder as a primary diagnosis—Less well known is that the symptoms of depersonalisation and derealisation can also occur as a chronic primary mental health disorder called depersonalisation derealisation disorder (DPRD). These symptoms can cause distress and affect quality of life and function. Case series from the UK,4 Germany,5 and the US6 find the primary disorder of DPRD affects men and women roughly equally. Several robust epidemiological surveys indicate prevalence rates over the past month of clinically significant DPRD at around 1% of the general population3 and at 5% within psychiatric outpatient samples.7 Data suggest that DPRD can be underdiagnosed, or the diagnosis is delayed, with patients typically waiting between seven and 12 years for a diagnosis.45 If left untreated the disorder can have an unremitting course lasting years. Patients report that early diagnosis and information-giving help alleviate the distress typically associated with this condition and promote recovery.

The infographic that accompanies this article summarises the main categories of people who experience depersonalisation and derealisation.

What symptoms do people describe?

Patients might use the language in Box 1 and infographic (see appendix files) when putting their experience into words. Such phrases used by patients might suggest the need for further questioning.

Box 1: What your patient might say

I feel as if I’m living in a dream

I feel like I don’t (or the world doesn’t) exist anymore

I feel completely detached from everything or everyone around me

It’s like I’m just watching life from behind glass/projected onto a screen/in a fog

I’m robotically going through the motions of being alive but feel dead inside

Alongside the core symptoms of unreality and detachment, people with depersonalisation and derealisation can describe emotional numbing of positive and negative emotions, and experiences affecting specific parts, or all, of their body. They might report that parts of their body (their reflection, voice, or hands) don’t feel like they belong to them and that their actions feel robotic. They might experience blurred vision or perceptual distortions, such as seeing the world in two dimensions. Obsessive existential thoughts about the meaning of life might be present. The person might complain about difficulty concentrating or remembering but these problems are typically not accompanied by clear-cut objective cognitive deficits such as memory or attention impairments on formal testing.8

Patients with depersonalisation and derealisation are aware that their experiences are subjective and do not reflect reality, but might present urgently seeking help because of fears that their symptoms indicate incipient psychosis or brain dysfunction. However, the “as if . . .”quality to their descriptions helps to distinguish those with depersonalisation and derealisation from those experiencing psychosis, as the former will not have accompanying hallucinations or delusional beliefs. In US psychiatric classification systems,9 depersonalisation derealisation disorder is categorised as a dissociative disorder due to the sense of detachment experienced. However it is distinguishable from other dissociative disorders in that discontinuities of memory and identity are rare.

What triggers depersonalisation and derealisation

Current evidence is insufficient to fully characterise or quantify associations with life events or other diagnoses, or to predict who will or won’t develop symptoms. However, what data exist suggest that there are some life events and diagnoses that are associated with transient or intermittent symptoms and with the more chronic disorder.

There is a strong association of depersonalisation or derealisation symptoms starting during a period of acute stress. This has led to the current understanding that DP DR is part of a normal physiological or psychological coping mechanism (“like a circuit breaker”) that is designed to protect us from overwhelming anxiety by creating a sense of detachment and numbing.1011 However, in some cases this normally transient coping mechanism can become maintained, leading to the chronic disorder of DPRD.11

How to assess and manage someone with symptoms

The suggested key principles for when someone presents with symptoms of depersonalisation or derealisation are laid out in the infographic (appendix files). This guide is compiled based on research evidence and clinical experience from authors based at the specialist London based NHS Depersonalisation Disorder Clinic. Try to distinguish between transient or intermittent symptoms; those that might be suggestive of a concurrent physical or mental health problem where the DP DR is secondary; or symptoms that are suggestive of the chronic disorder of DPRD. Remember DPRD can be a primary disorder or it can be a comorbid problem in the context of substantial history of trauma or a primary mental health disorder. If the latter, then address this history. If there is no significant history of trauma then treat as a primary disorder by following the guidance in this article.

Assessing symptoms of DP DR—The hardest differential diagnosis is when both an anxiety disorder and depersonalisation derealisation disorder are present and distressing. In these cases it is worthwhile monitoring both conditions on a monthly basis, and if the DP DR does not resolve within a few months, to assume that this is primary DPRD, and to follow the recommendations for this. Box 2 shows a scoring system to assist with assessment of DP DR symptoms.

Box 2: Assessing DP DR symptoms

The presence and severity of symptoms can be assessed by summing scores on two questions:

“Over the past two weeks, how often have you been bothered by the experience of

Your surroundings feeling detached or unreal, as if there were a veil between you and the outside world

Out of the blue, you feel strange, as if you were not real or as if you were cut off from the world.”

Scale: 0=not at all; 1=several days; 2=more than half the days; 3=nearly every day.

Clinical cut off score of >=3

Scores above the cut off can identify those with symptoms that reach a clinical level of severity (or to help diagnose pathological DPDR symptoms).

You can also ask your patient to complete the 29 item Cambridge Depersonalisation Scale12 (available for free through internet search). Scores of >=70 are associated with clinical severity. Those diagnosed with primary DPRD are likely to need specifically targeted intervention for DPRD.

Management of DP DR symptoms—In all cases, when there are DP DR symptoms present, normalise these symptoms by explaining the common association with acute stress and fatigue, as well as giving hope that these symptoms are likely to resolve in time. Signpost patients to sources of support (see Box ‘Patient resources’).

Treatment for primary depersonalisation derealisation disorder—The evidence base for empirically validated treatments for DPRD is extremely limited. Small open studies suggest some interventions may be promising, but need to be treated with caution. Psychotherapeutic approaches such as cognitive behavioural therapy, specifically adapted for DPRD, have shown good results but are only available in specialist settings.13 Mindfulness approaches could be beneficial.14 A study of lamotrigine as an adjunct therapy reported dose related benefits,15 as did studies using opiate antagonists.1617 Repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation has also been tried and the results show promise.1819

The older literature confirms the large number of treatments tried but ineffective, including anticonvulsants, stimulants, and even electroconvulsive therapy.20 A recent systematic review21 found only three double blind randomised control trials (RCTs), with inconsistent results. One RCT involved lamotrigine, which blocks ketamine induced depersonalisation.22 The second trial had no effect, albeit approaching statistical significance.23 An RCT of fluoxetine found it no more efficacious than placebo,24 although with a trend for efficacy in those with a comorbid anxiety disorder. An RCT using biofeedback found no significant therapeutic benefit.25

Personal account

I smoked cannabis one evening while at university. I had smoked once before, a year earlier. Shortly after, I began to feel as though my eyes were fixating on parts of the room, and that I was distanced from my environment. This led to me having a panic attack which was only alleviated when I eventually managed to sleep. In the morning I continued to feel distanced, and as though I was a spectator in my own life. I experienced this constantly for many months. Recovery was a gradual process, firstly of being distracted from the feelings of depersonalisation for longer and longer periods while I was engaged in activities, and then later experiencing extended periods where I was actually conscious of feeling present in the moment. Diagnosis was an important part of my recovery, as was continuing with some normal, daily activities, and distracting myself with engaging activities. Cognitive behavioural therapy and mindfulness techniques provided me with the tools to manage the underlying anxiety. My DPDR did not disappear overnight, it was a gradual process of trusting in the techniques and applying them every day, and learning coping mechanisms to manage the distressing symptoms in the meantime.

Personal account

My depersonalisation started after severe anxiety with acute physical symptoms. I started being hyper aware of my every movement, word, and breath. When I looked at my hands they felt like they didn't belong to me, my voice was like it was not my own, and I was totally detached looking in a mirror. It was as if I was living in a dream, my head felt very foggy, and I was very numb. I remember at its worse that I would laugh or cry but feel nothing. Already suffering from anxiety, once I fell into the depersonalisation as well I very quickly was on a hamster wheel: I worried about this feeling, which of course fed my anxiety. I couldn't eat or sleep or enjoy anything anymore.

I was put on antidepressants, which helped with the anxiety, and I have been on them ever since (around 20 years). True recovery only started to come to me when, very luckily, I managed to get in touch with a clinical psychologist. I started cognitive behavioural therapy (CBT) specialising in depersonalisation and anxiety, which taught me to not be scared and run away from the feelings. Once I understood what this condition was, and was told it is actually very common and there were lots of people out there like me that had experienced similar symptoms, and most importantly recovered, I started to feel a lot calmer about it, and it felt less like I was being attacked by some strange force.

For me it is 100% my anxiety issues that brought it on. Even now when I suffer with anxiety it can come back, but because I am not scared of it anymore it always fades again. For recovery I firmly believe quick and correct diagnosis is imperative, as well as having someone that understands what you are thinking and feeling. CBT has actually changed my life and the way I think about things and I feel this is a huge part of recovery. Having interests and a job and my beautiful son has also got me through the hard times, as distraction can really help. Another thing that has helped me is telling people, I kept the fact that I had depersonalisation a secret for years, as I felt like it was too strange a thing to talk about. I thought people would think I was mad, but actually when you tell someone they are pretty unimpressed in the way that it’s not a big deal at all. To summarise, I would say the following four things help the most with getting over my depersonalisation: knowledge, acceptance, distraction, and calmness.

Education into practice

Did you know that when patients say things like “I don’t feel real” they may be suffering from depersonalisation disorder?

Do you know where to refer patients if you suspect they might be suffering from depersonalisation derealisation disorder?

Patient involvement

The article was co-written by a patient with longstanding DPRD who contributed at every stage in the process. We also had another patient contributor and a patient reviewer.

The patients wished to emphasise the importance of clinicians recognising that DP DR symptoms can occur as a primary diagnosis, distinct from anxiety and depression, as so many people with DP DR symptoms are misdiagnosed resulting in distress and delay in treatment. They also wanted to stress that although there is no definitive treatment, recovery is possible for many people with DPRD.

Patient resources

Self help book

Overcoming Depersonalisation and Feelings of Unreality, Baker, Hunter, Lawrence and David, Robinson Press. ISBN-13: 978-1845295547

Online information

Phone support

Rethink Advice and Information service: 0300 5000 927

Further reading

Sierra M. Depersonalization: A new look at a neglected syndrome. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press; 2009.

Simeon D, Abugel J. Feeling Unreal: Depersonalization Disorder and the Loss of Self. Oxford: Oxford University Press; 2006

Harris Goldberg. Numb [DVD]. US: IMDb; 2007

Footnotes

We have read and understood BMJ policy on declaration of interests and declare the following interests: none.

Patient consent obtained.

Provenance and peer review: commissioned, based on an idea from the author; externally peer reviewed

Contributors: ECMH took the lead on the writing of this article, with other authors contributing. ECMH is the guarantor. We would like to thank Professor Andre Tylee for his comments on this paper and Sarah Ashley for her contribution.