Intended for healthcare professionals

Rapid response to:

Analysis

Why cancer screening has never been shown to “save lives”—and what we can do about it

BMJ 2016; 352 doi: https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.h6080 (Published 06 January 2016) Cite this as: BMJ 2016;352:h6080

Including all mortality

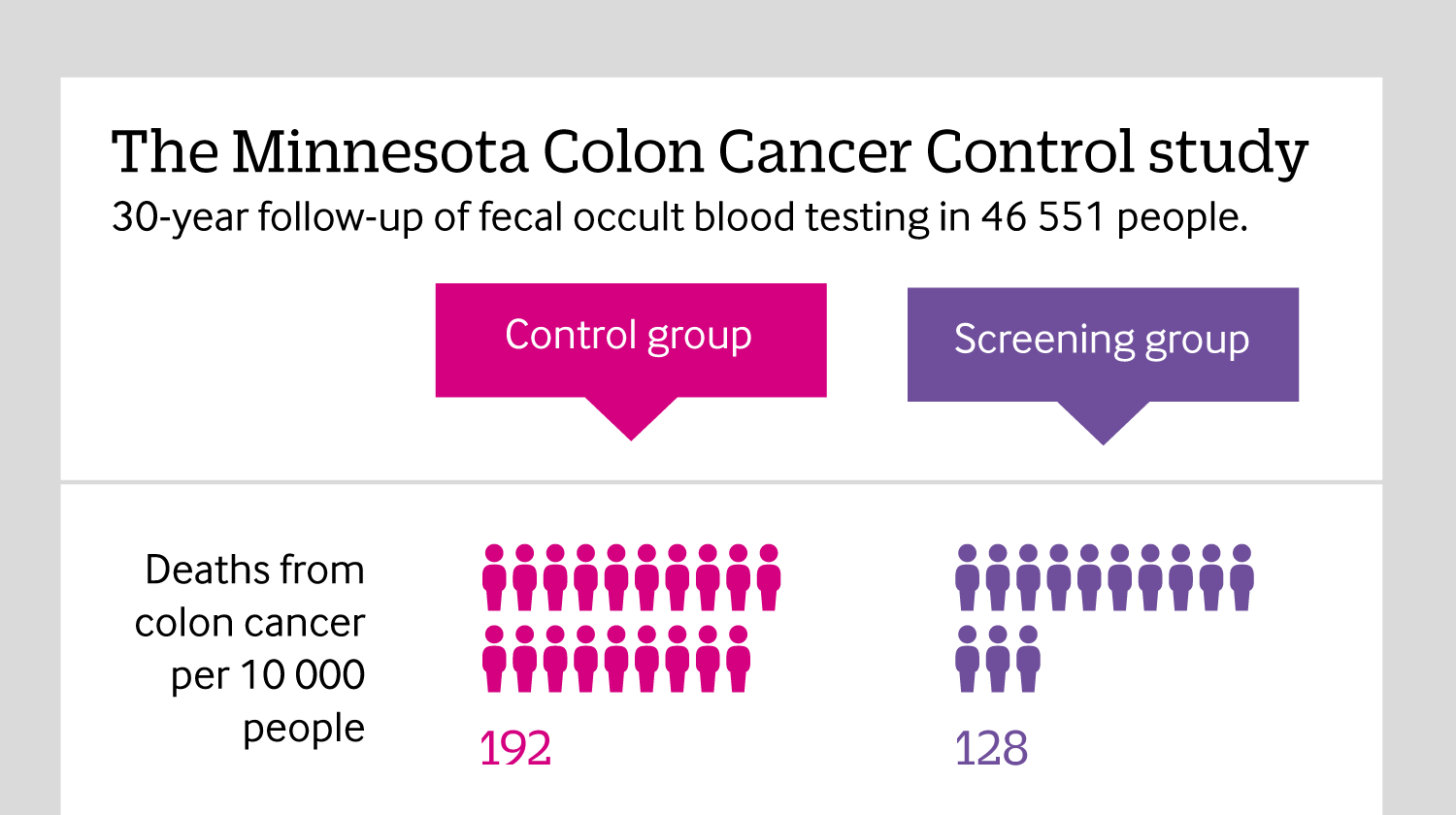

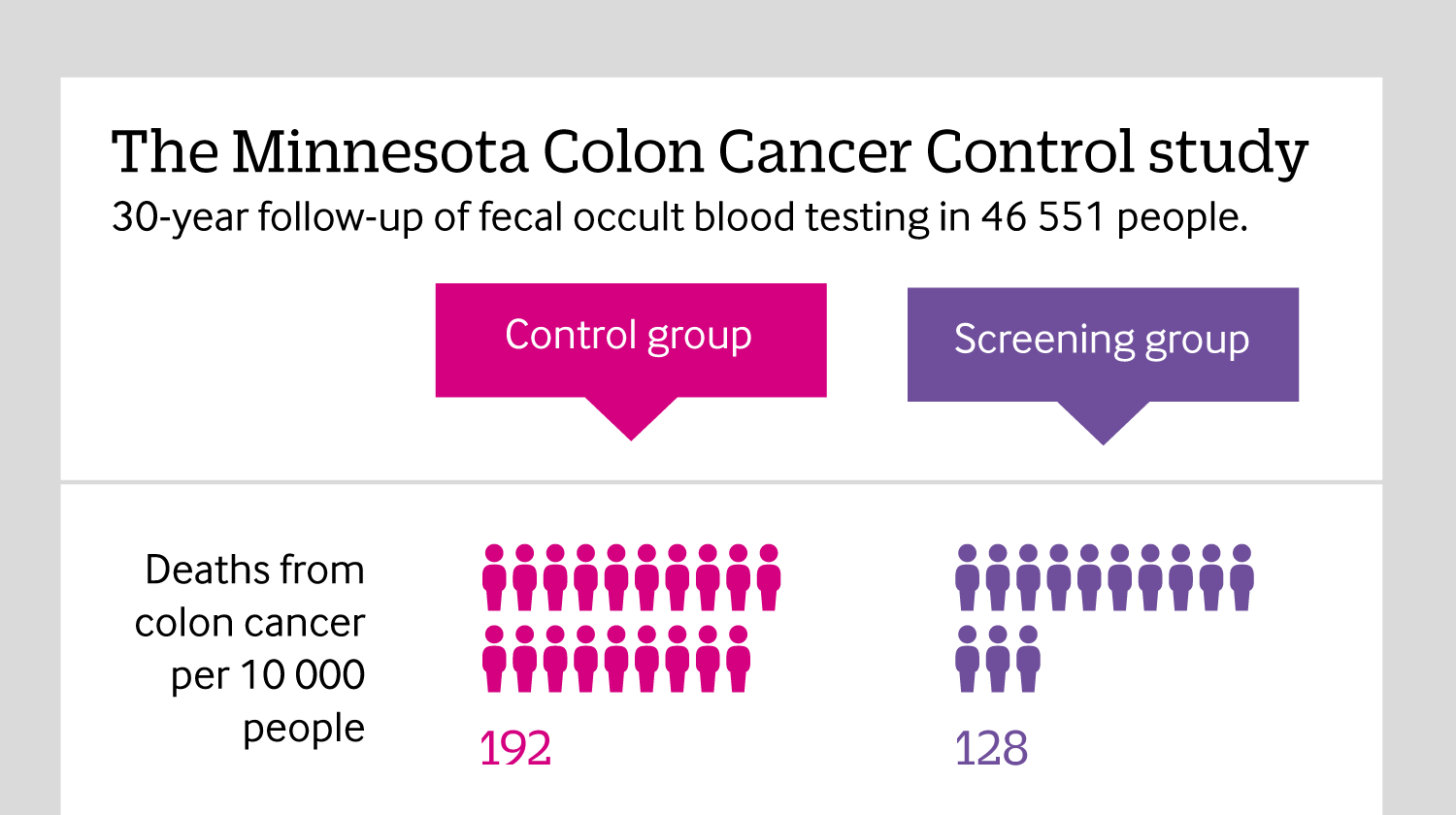

Click here to see an infographic, explaining why reporting all causes of mortality in cancer screening trials is so important.

Rapid Response:

Biopolitics – preventive diagnostics and the ethics of sacrificing one life for another.

This is a very useful article and should be widely read, but I want to draw attention to the ethics of always necessarily sacrificing some lives in order to preserve others.

My comment here explores the ethics of screening and predictive diagnostics from a (up til now) neglected biopolitical perspective. It introduces an academic domain that up to now has had little inter-disciplinary overlap with Evidence Based Medicine. And although some of the language and concepts here may seem a little esoteric I would ask you to persevere. This concerns the domain of Biopolitics. Biopolitics explores the relation, and the effects of this relation, between the political order (ideologies if you like, increasingly neoliberal today) and Bíos, a term used by Esposito to describe a biological life conforming to and objectvised by the political order (Esposito, 2008a, b).

Medical screening to measure the risks of, and to prevent, future ill health is an example of what the Italian philosopher Esposito, in his book Bíos, has identified as an immunitary mechanism that functions, ostensibly, in the name of 'preserving life'. (Esposito 2008a) However this function, Esposito claims, is only secondary to its primary function, which is to act as a kind of biopolitical glue binding together and maintaining and reproducing the political order (today - neoliberalism) with a biological life of a subject (bíos) that is subjugated to and is an object for this political order. Biological Life's innate instability over time and neoliberalism's demand for economic growth lead to an ongoing intensification of these mechanisms. The paper by Prasda et al (Prasad, Lenzer, and Newman, 2016) is a very useful demonstration of the coincident sacrifice and destruction of life that can only increase as the immunitary mechanisms intensify. Esposito might claim (on the basis of his writings in Bíos) that only the development of a new ethical relationship to life itself by the medical profession and patients, that begins to refuses the sacrifice of one life for another, will slow this process down. In addition a fundamental break with neoliberalism’s influence on medical practice would also address the impact of politics on so-called patients' 'values'- values not at present generated by the individual but constituted by a subject subjugated by the political order.

As in this paper by Prasad et al(Prasad et al., 2016) the resistance to such destructive mechanisms focuses mostly on regulation, bigger studies, 'more honesty' and shared decision making (SDM). But we can see that these, alone, can and will never succeed in preventing an increasingly destructive (even thanatopolitical) process. These strategies may even function, given biopolitical politico-economic imperatives and power, to legitimate further intensifications in the longer run.

These resistive measures do not address the biopolitical and therefore the structurally neccessary 'tremendous prophylactic' (Nietzsche 1986) p113 immunitary drivers that maintains the subjugation of the population necessarily and reciprocally bound to and maintaining the existing social order and its socio-economic inequalities.

“….. against the vacuum of sense that opens at the heart of life that is ecstatically full of itself, the general process of immunization is triggered…. ‘the democratization of Europe is, it seems, a link in the chain of those tremendous prophylactic measures which are the conceptions of modern times.’” (Esposito, 2008a) p89, cites (Nietzsche, 1986) p113

Yes, medical practice, sometimes ethically, prevents suffering more or less in two ways a) the suffering today and b) preventing suffering tomorrow. But is it always ethical if it involves sacrificing one life for another, and when an individual does not know whether his body is being preserved or sacrificed or even both. Resistance to the excess of destruction is an important but biopolitical struggle. However the efforts by those resisting screenings excesses focus on a struggle that is not seen for what it is. On the surface are the effects of systems using forms of biological knowledge in a struggle between a) interventions for profit and power, and b) non-intervention, sacrificing power and profit. But this is secondary to the primary biopolitical struggle: between a) preserving an anticipated future life by eradicating risk, versus b) allowing a life today to take its chances and face risk, or if you like between preserving by sacrificing life or nor preserving life. Preventive screening and predictive medical interventions can either preserve life now or life in the future but either way must entail more or less sacrifice, destruction and weakening of life. New questions, language and strategies for medicine can emerges from Esposito's writings such: Is the intervention necessary? is it always ethical to weaken one life in order to strengthen another? Is it ethical to divide lives ‘worth living’ from ‘lives not worth living’ on economic grounds?

The French doctor and philosopher (and French resistance activist fighting the Nazis) Canguilhem introduced the idea of normative man, and life itself as its own norm, not a panacea in itself but worth consideration:

“health is in no way a demand of the economic order that is to be weighed when legislating, but rather is the spontaneous unity of the conditions for the exercise of life.” (Esposito, 2008a) p189 citing Canguilhem ‘Une pédagogie de la guérison est-elle possible?’ In ‘Écrits sur la medicine’ (Paris editions, du Seuil, 2002, p89)

Esposito, R. (2008a) Bios: Biopolitics and Philosophy. Minneapoli: University of Minnesota.

Esposito, R. (2008b) The Immunization Paradigm. diacritics, 36(2): 23-48.

Nietzsche, F.W. (1986) Human, All Too Human. A Book For Free Spirits. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Prasad, V., Lenzer, J., & Newman, D. (2016) Why cancer screening has never been shown to “save lives”—and what we can do about it. BMJ, 352.

Competing interests: No competing interests