Abstract

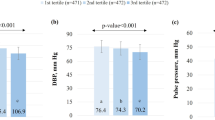

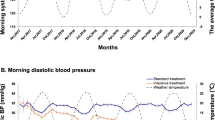

Recommendations for control of high blood pressure (BP) emphasize lifestyle modification, including weight loss, reduced sodium intake, increased physical activity, and limited alcohol consumption. The Dietary Approaches to Stop Hypertension (DASH) dietary pattern also lowers BP. The PREMIER randomized trial tested multicomponent lifestyle interventions on BP in demographic and clinical subgroups. Participants with above-optimal BP through stage 1 hypertension were randomized to an Advice Only group or one of two behavioural interventions that implement established recommendations (Est) or established recommendations plus DASH diet (Est plus DASH). The primary outcome was change in systolic BP at 6 months. The study population was 810 individuals with an average age of 50 years, 62% women, 34% African American (AA), 95% overweight/obese, and 38% hypertensive. Participants in all the three groups made lifestyle changes. Mean net reductions in systolic (S) BP in the Est intervention were 1.2 mmHg in AA women, 6.0 in AA men, 4.5 in non-AA women, and 4.2 in non-AA men. The mean effects of the Est Plus DASH intervention were 2.1, 4.6, 4.2, and 5.7 mmHg in the four race–sex subgroups, respectively. BP changes were consistently greater in hypertensives than in nonhypertensives, although interaction tests were nonsignificant. The Est intervention caused statistically significant BP reductions in individuals over and under age 50. The Est Plus DASH intervention lowered BP in both age groups, and significantly more so in older individuals. In conclusion, diverse groups of people can adopt multiple lifestyle changes that can lead to improved BP control and reduced CVD risk.

This is a preview of subscription content, access via your institution

Access options

Subscribe to this journal

Receive 12 digital issues and online access to articles

$119.00 per year

only $9.92 per issue

Buy this article

- Purchase on Springer Link

- Instant access to full article PDF

Prices may be subject to local taxes which are calculated during checkout

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Whelton PK et al. Primary Prevention of Hypertension. Clinical and public health advisory from the National High Blood Pressure Education Program. JAMA 2002; 288: 1882–1888.

Joint National Committee on Prevention, Detection, Evaluation, and Treatment of High Blood Pressure. The Sixth Report of the Joint National Committee on the Prevention, Detection, Evaluation, and Treatment of High Blood Pressure (JNC-VI). Arch Intern Med 1997; 157: 2413–2446.

Appel LJ et al. A clinical trial of the effects of dietary patterns on blood pressure. N Engl J Med 1997; 336: 1117–1124.

Karanja NM et al. Descriptive characteristics of the dietary patterns used in the Dietary Approaches to Stop Hypertension trial. J Am Diet Assoc 1999; 99(Suppl): S19–S27.

Chobanian AV et al. The seventh report of the Joint National Committee on Prevention, Detection, Evaluation, and Treatment of High Blood Pressure: the JNC 7 report. JAMA 2003; 289: 2560–2572.

Appel LJ et al. Effects of comprehensive lifestyle modification on blood pressure control: main results of the PREMIER clinical trial. JAMA 2003; 289: 2083–2093.

Weinberger MH et al. Definitions and characteristics of sodium sensitivity and blood pressure resistance. Hypertension 1986; 8: II127–II134.

Weinberger MH, Fineberg NS . Sodium and volume sensitivity of blood pressure. Age and pressure change over time. Hypertension 1991; 18: 67–71.

Sacks FM, et al, for the DASH-Sodium collaborative research group. A clinical trial of the effects on blood pressure of reduced dietary sodium and the DASH dietary pattern (The DASH-Sodium Trial). N Engl J Med 2001; 344: 3–10.

Vollmer WM, et al, for the DASH-Sodium Collaborative Research Group. Effects of dietary patterns and sodium intake on blood pressure: subgroup analysis of the DASH-sodium trial. Ann Int Med 2001; 135: 1019–1028.

Svetkey LP et al. Effects of dietary patterns on blood pressure: subgroup analysis of the Dietary Approaches to Stop Hypertension (DASH) randomized clinical trial. Arch Intern Med 1999; 159: 285–293.

Svetkey LP et al. PREMIER: a clinical trial of comprehensive lifestyle modification for blood pressure control: rationale, design and baseline characteristics. Ann Epidemiol 2003; 13: 462–471.

Karanja NM et al. Descriptive characteristics of the dietary patterns used in the Dietary Approaches to Stop Hypertension Trial. DASH Collaborative Research Group. J Am Diet Assoc 1999; 99: S19–S27.

Bandura A . Social Foundations of Thought and Action: A Social Cognitive Theory. Prentice-Hall: Englewood Cliffs, NJ, 1986.

Watson DL, Tharp RG . Self-directed Behavior: Self-modification for Personal Adjustment, 5th ed. Brooks/Cole: Pacific Grove, CA, 1989.

Prochaska JO, DiClemente CC . Stages and processes of self-change of smoking: toward an integrative model of change. J Consult Clin Psychol 1983; 51: 390–395.

The Trials of Hypertension Prevention Collaborative Research Group. The effects of nonpharmacologic interventions on blood pressure of persons with high normal levels. JAMA 1992; 267: 1213–1220.

ACSM—American College of Sports Medicine. ACM's Guidelines for Exercise Testing and Prescription, 5th ed. Williams and Wilkins: Media, PA, 1995.

Rose G, McCartney P, Reid DD . Self-administration of a questionnaire on chest pain and intermittent claudication. Br J Prev Soc Med 1977; 31: 42–48.

Blair SN et al. Assessment of habitual physical activity methodology by a seven-day recall in a community survey and controlled experiments. Am J Epidemiol 1986; 122: 794–804.

Fox TA, Heimendinger J, Block G . Telephone surveys as a method for obtaining dietary information: a review. J Am Diet Assoc 1992; 92: 729–732.

TOHP Research Group. The effects of nonpharmacologic interventions on blood pressure of persons with high normal levels. Results of the Trials of Hypertension Prevention, Phase I. JAMA 1992; 267: 1213–1220.

Whelton PK, et al, for the TONE Collaborative Research Group. Efficacy of sodium reduction and weight loss in the treatment of hypertension in older persons: main results of the randomized, controlled trial of nonpharmacologic interventions in the elderly (TONE). JAMA 1998; 279: 839–846.

Weinberger MH, Fineberg NS . Sodium and volume sensitivity of blood pressure. Age and pressure change over time. Hypertension 1991; 18: 67–71.

The Trials of Hypertension Prevention Collaborative Research Group. Effects of weight loss and sodium reduction intervention on blood pressure and hypertension incidence in overweight people with high-normal blood pressure. The Trials of Hypertension Prevention, phase II. Arch Intern Med 1997; 157: 657–667.

Stevens VJ et al. Long-term weight loss and changes in blood pressure: results of the trials of hypertension prevention, phase II. Ann Intern Med 2001; 134: 1–11.

Kumanyika SK, Obarzanek E, Stevens VJ, Hebert PR, Whelton PK . Weight-loss experience of black and white participants in NHLBI-sponsored clinical trials. Am J Clin Nutr 1991; 53(Suppl): S1631–S1638.

Ard JD, Carter-Edwards L, Svetkey LP . A new model for developing and executing culturally appropriate behavior modification clinical trials for African Americans. Ethn Dis 2002; 13: 279–285.

Lin P-H et al. The DASH diet and sodium reduction improve markers of bone turnover and calcium metabolism in adults. J Nutr 2003; 133: 3130–3136.

ACS (American Cancer Society). Guidelines on diet, nutrition, and cancer prevention: reducing the risk of cancer with healthy food choices and physical activity. The American Cancer Society 1996 Advisory Committee on Diet, Nutrition, and Cancer Prevention. CA Cancer J Clin 1996; 46: 325–341.

NIH Consensus Development Panel on Optimal Calcium Intake. NIH Consensus conference. Optimal calcium intake. JAMA 1994; 272: 1942–1948.

Acknowledgements

We are extremely grateful to our participants for their sustained commitment to the trial. We also thank Eva Obarzanek, PhD, Jeffrey A Cutler, MD, Michael Proschan, PhD, and Denise Simons-Morton, MD, PhD, at NHLBI for their valuable contributions to the design of PREMIER, and thank the members of the Data, Safety and Monitoring Board that included Jerome D Cohen (chair), Nancy R Cook, ScD, Patricia Dubbert, PhD, Keith C Ferdinand, MD, Jim Raczynski, PhD, and Linda Van Horn, PhD. We thank Christine Pfeiffer PhD, Chief, NHANES and Global Micronutrient Laboratory; Elaine W Gunter MT, Deputy Director, Division of Laboratory Sciences, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; Thomas G Cole, PhD, Director, Core Laboratory for Clinical Studies, Washington University in St. Louis; Helen S Wright, PhD, Principal Investigator, Pennsylvania State University Diet Assessment Center; Diane C Mitchell, Investigator, Pennsylvania State University Diet Assessment Center; Shiriki Kumanyika, PhD, MPH, Center for Clinical Epidemiology and Biostatistics, University of Pennsylvania School of Medicine; Jerome Williams, PhD, Howard University; Leslie Pruitt, PhD, Stanford Center for Research in Disease Prevention, Stanford University School of Medicine; and Abby King, PhD.

In addition, we extend our appreciation to individuals at each of the participating sites.

From the Coordinating Center, Center for Health Research, Portland, OR: Mikel Aickin, PhD, Jack Hollis, PhD, Njeri Karanja, PhD, Fran Heinith, BSN, Kristy Funk, MS, RD, Michael Allison, BS, Chuhe Chen, PhD, Clifton Hindmarsh, MS, Terry Kimes, MS, Wan-Ru Li, MBA, Gayle Meltesen, MS, Carrie Meeks, Nadia Redmond, MSPH, Rina Smith, BA, PgDipLGA.

From Duke University Medical Center, Durham, NC: Colleen McBride, PhD, Jamy Ard, MD, Kathleen Aicher, Blondeaner Brown, Denise Ernst, Jeanne Gresko, Madhuri Kesari, Femke Lamers, LaTonya Nealon, Tori Phelps, LaVerne Pruden, LaChanda Reams, Patrice Reams, Benjamin Reese PsyD, Fran Rukenbrod, Sonia Steele, Natalie Thorpe, Olaunda Williams, Chenghua Yang.

From Pennington Biomedical Research Center, Baton Rouge, LA: Philip Brantley, PhD, Allison Worthen, Betty Kennedy, PhD, Emily Griffin, Erma Levy, Terri Keller, Shantell Jones, Katherine Lastor.

From Johns Hopkins Medical Center, Baltimore, MD: Barbara Bailey, MS, RD, Jeanne Charleston, RN, MSN, Sharrone Cypress, Arlene Dalcin, MS, RD, Maura Deeley, Charalett Diggs, RN, Thomas P Erlinger, MD, MPH, Ann Fouts, RN, Angela Hall, Charles Harris, Tara Harrison, Megan Jehn, Shirley Kritt, Estelle Levitas, Phyllis McCarron, MS, RD, Edgar R Miller, III, MD, PhD, Pauline Patrick, LD, Charles Powell, Thomas Shields, LeeLana Thomas, MS, RD, Letitia Thomas, Bobbie Weiss, Deborah Young, PhD.

From the Center for Health Research clinical site, Portland, OR: Adrianne C Feldstein, MD MS, Daniel S Laferriere, RN, MSN, Shirley R Craddick, RD MHA, Dana R Larson, RD, MS, Diane J Cook, RD, MPH, Carol L Young, Susan D Arnold, RN, BSN, Donna L Clark, Stanley B Postlethwaite, Titza Suvalcu-Constantin, Carol M Maul, Donna M Gleason, Cheryl A Johnson Ed. M, Pamela G McNeal, Debra D Burch.

This work is supported by the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute, NIH grants UO1 HL60570, UO1 HL60571, UO1 HL60573, UO1 HL60574, UO1 HL62828.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Svetkey, L., Erlinger, T., Vollmer, W. et al. Effect of lifestyle modifications on blood pressure by race, sex, hypertension status, and age. J Hum Hypertens 19, 21–31 (2005). https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.jhh.1001770

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.jhh.1001770

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

Heart 2 Heart: Pilot Study of a Church-Based Community Health Worker Intervention for African Americans with Hypertension

Prevention Science (2023)

-

The Weight of Racial Discrimination: Examining the Association Between Racial Discrimination and Change in Adiposity Among Emerging Adult Women Enrolled in a Behavioral Weight Loss Program

Journal of Racial and Ethnic Health Disparities (2022)

-

Responding to Health Disparities in Behavioral Weight Loss Interventions and COVID-19 in Black Adults: Recommendations for Health Equity

Journal of Racial and Ethnic Health Disparities (2022)

-

Treatment outcomes among adults with HIV/non-communicable disease multimorbidity attending integrated care clubs in Cape Town, South Africa

AIDS Research and Therapy (2021)

-

Effectiveness of a patient-centered medical home model of primary care versus standard care on blood pressure outcomes among hypertensive patients

Hypertension Research (2020)