Abstract

This study examines trends in antidepressant drug dispensations among young people aged 0–24 years in Sweden during the period 2006–2013, as well as prescription patterns and central nervous system (CNS) polypharmacy with antidepressants. Using linkage of Swedish national registers, we identified all Swedish residents aged 0–24 years that collected at least one antidepressant prescription (here defined as antidepressant users) between 1 January 2006 and 31 December 2013 (n = 174,237), and categorized them as children (0–11 years), adolescents (12–17 years), and young adults (18–24 years). Prevalence of antidepressant dispensation rose from 1.4 to 2.1% between 2006 and 2013, with the greatest relative increase in adolescents [by 97.8% in males (from 0.6 to 1.3%) and by 86.3% in females (from 1.1 to 2.1%)]. Most individuals across age categories were prescribed selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors, received their prescriptions from psychiatric specialist care, and had treatment periods of over 12 months. Prevalence of CNS polypharmacy (dispensation of other CNS drug classes in addition to antidepressants) increased across age categories, with an overall increase in prevalence from 52.4% in 2006 to 62.1% in 2013. Children experienced the largest increase in polypharmacy of three or more psychotropic drug classes (4.4–10.1%). Anxiolytics, hypnotics, and sedatives comprised the most common additional CNS drug class among persons who were prescribed antidepressants. These findings show that the dispensation of antidepressants among the young is prevalent and growing in Sweden. The substantial degree of CNS polypharmacy in young patients receiving antidepressants requires careful monitoring and further research into potential benefits and harms.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Mood and anxiety disorders are common mental problems in young individuals [1, 2] and may contribute to both short- and long-term adverse outcomes—including decreased quality of life, lower school performance, and suicide in severe cases [3–6]. Antidepressants are the main pharmacological treatment option available and have become increasingly common in several Western settings [7–10]. For example, the prevalence of receiving antidepressant prescriptions in those aged 0–19 years rose by 54.4% in the UK (from 0.7 to 1.1%) and by 49.2% in Germany (from 0.3 to 0.5%), during 2005–2012 [8]. Despite this, safety concerns about antidepressant use in this age group have been raised—with reports on increased risks of adverse outcomes such as violence [11], akathisia [12], and suicidality [13–15]. In 2004, the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) issued a “black box” warning to highlight potential risks of antidepressants in individuals aged up to 18 years. In 2007, this warning was extended to those aged up to 25 years [14, 16]. Similar warnings were issued across Europe in the same period—for example, by the European Medicines Agency in 2005 [8].

In light of these safety concerns, it is important to monitor the risks and benefits of antidepressant use among the young. This entails documenting changes in the prevalence of dispensation, as well as clinical prescription patterns—including the source of prescription, treatment duration, and use of other central nervous system (CNS) drugs. CNS polypharmacy is of particular importance, as the safety and efficacy of combining psychotropic drug classes are not well established [17], with adverse effects including cumulative toxicity and drug interactions [18]. A US population-based study found that psychotropic polypharmacy of two drugs was associated with a 17% higher average number of side effects, while polypharmacy with three or more drugs was associated with a 38% higher average number, compared with monopharmacy [19]. Adverse outcomes resulting from polypharmacy may be compounded among the young, which comprise a potentially vulnerable population where the effects of individual drugs, let alone combinations of them, are not conclusively established. Many psychotropic drugs are also prescribed off-label in this age group—40.9% of all antidepressant prescriptions in German 0- to 17-year-olds were estimated to be off-label in 2011 [20]. The prevalence of CNS polypharmacy generally is understudied, although there is evidence that it has increased in certain settings. For example, among US outpatient visits where a psychiatric diagnosis was made, the percentage with prescriptions of psychotropic medications from two or more drug classes increased from 22.2% in 1996–1999 to 32.2% in 2004–2007 [21]. Recent studies on CNS polypharmacy among young antidepressant users in a European population are lacking.

Documenting the clinical patterns of antidepressant dispensations among the young has implications for the development of appropriate treatment guidelines, as well as for future research on the benefits and harms of antidepressant drugs in a potentially vulnerable age group. The present study therefore examines antidepressant dispensations among children, adolescents, and young adults in Sweden between 2006 and 2013—investigating patterns of type of antidepressant medication, source of prescription, treatment duration, and CNS polypharmacy.

Methods

National registers and study population

We linked information from three Swedish national registers based on unique personal identification numbers [22]. The first was the Swedish Prescribed Drug Register (PDR), which covers data on all dispensed pharmaceuticals in Sweden since July 2005, including drug identity [registered using Anatomical Therapeutic Chemical (ATC) codes], dose, dates of dispensed prescriptions, and the prescriber’s profession and practice [23]. The proportion of invalid dispensation entries in the PDR is expected to be below 2% [24]. The second was the National Patient Register, which contains information on all admissions to inpatient hospital care since 1973 and admission to outpatient specialists since 2001 [25], with information on all discharge diagnoses in accordance with International Classification of Disease (ICD) codes. Diagnosis data from the National Patient Register have good to excellent validity for a range of conditions, including depression, bipolar disorder, and schizophrenia [26–28]. The third was the Total Population Register, which includes demographic information on all Swedish residents since 1968, and has virtually complete coverage of births and deaths [29].

The target population included all individuals aged up to 25 years who were residing in Sweden at some point during the period between 1 January 2006 and 31 December 2013. The period from 1 July to 31 December 2005 was not used to allow for complete yearly data.

Within the target population, we selected all individuals who had at least one dispensed prescription of antidepressant drugs (ATC code: N06A) during the study period. We also created a 1:1 randomly selected control group of antidepressant non-users from the Total Population Register by matching the antidepressant users by year of birth and sex, to compare how psychiatric comorbidity profiles of antidepressant users differed from those of non-users between age groups.

Measures

Antidepressant use was defined as dispensation of antidepressant drugs (ATC code: N06A) from the PDR. The antidepressants were grouped as: tricyclic antidepressants (TCAs; N06AA); selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs; N06AB); serotonin–norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors (SNRIs; N06AX16 or N06AX21); monoamine oxidase inhibitors (MAOI; N06AF or N06AG); and others (other N06A drugs) (Supplementary Table 1). From the PDR, we also retrieved information on the source of prescription (primary care/non-psychiatric specialist care/psychiatric care) and the duration of prescription [single dispensation, short term (≤ 6 months), medium term (6–12 months), and long term (> 12 months)] (24). We considered an individual to be receiving treatment during the interval between two dispensed antidepressant prescriptions, unless dispensed prescriptions occurred more than 6 months apart (25). If multiple treatment periods occurred during a year, the longest treatment period for each individual was considered.

Use of CNS drugs concurrently with an antidepressant prescription was defined as a dispensed prescription of at least one other CNS medication within 6 months of a dispensed antidepressant prescription. The other CNS drugs considered were: antipsychotics (N05A); anxiolytics, hypnotics, and sedatives (N05B or N05C); attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) medication (N06B); drugs used in addictive disorders (N07B); opioids and pain medications (N02A); and antiepileptic drugs (N03A).

Statistical analyses

We described trends in antidepressant dispensation by calculating the prevalence of dispensation by year for the period 2006–2013, overall and stratified by sex and age group [“children” (0–11 years), “adolescents” (12–17 years), and “young adults” (18–24 years)]. A Cochran–Armitage test for trend was performed. Antidepressant dispensation patterns for the year 2013 were presented in relation to antidepressant type, source of prescription (primary care/non-psychiatric specialist care/psychiatric care), and duration of prescription.

Central nervous system polypharmacy is here defined as a dispensed prescription of one or more other CNS drugs within 6 months of the dispensed antidepressant prescription [30]. The degree of CNS polypharmacy among patients receiving antidepressants over the study period was assessed by calculating the proportion of antidepressant users with different numbers of classes of other CNS drugs (0, 1, 2 or ≥ 3) from 2006 to 2013, stratified by age group.

We further examined the proportion of individuals collecting other CNS drugs among patients receiving antidepressants in the year 2013. Odds ratios (ORs) for the collection of other CNS drugs in those with dispensed antidepressant prescriptions versus controls were calculated by age group, using logistic regression models with adjustment for sex and age as a categorical variable (in 1-year bands) and presented alongside 95% confidence intervals (CIs) [31]. We also calculated the frequency of psychiatric disorders in individuals with dispensed antidepressants for the year 2013, alongside ORs for a given disorder in individuals dispensing antidepressants versus non-users. Psychiatric disorders were defined as diagnoses made prior to or during the year of the dispensed antidepressant prescription, including depression (ICD-10 codes: F32–F39), bipolar disorder (F30–F31), anxiety disorder (F40–F48), schizophrenia spectrum disorder (F20–F29), substance use disorder (F10–F19), personality disorder (F60–F61), ADHD (F90), and other developmental or childhood disorders (F80–F98, excluding F90).

All statistical analyses were performed using SAS version 9.4 (SAS Institute). Figures were created in R version 3.5.0.

Results

Time trends in antidepressant use

We identified 174,237 individuals resident in Sweden who received at least one prescription at any age below 25 years during 2006–2013. Table 1 shows the prevalence of antidepressant dispensation by year as stratified by age and sex. For the overall population, there was an increase in antidepressant dispensation, from 1.4% in 2006 to 2.1% in 2013 (Table 1). The greatest relative change in prevalence of antidepressant dispensation was in adolescents (by 97.8% in males, from 0.6 to 1.3%, and by 86.3% in females, from 1.1 to 2.1%). However, young adults (18–24 years) had the greatest prevalence overall (3.6% for males and 7.0% for females in 2013). With regard to the type of antidepressant, the greatest relative change in prevalence was in the dispensation of other antidepressants (by 89.3%, from 0.2 to 0.4%), followed by SNRIs (80.5%, from 0.1 to 0.2%) and TCAs (52.5%, from 0.06 to 0.10%; Supplementary Table 2). The most common antidepressant in 2013 across age groups was sertraline (accounting for 62.8, 29.0, and 28.6% of dispensed prescriptions in children, adolescents, and young adults, respectively), followed by fluoxetine in the youngest two age categories, but by citalopram in the young adults (Supplementary Table 3). Sertraline, fluoxetine, amitriptyline, and fluvoxamine are the only antidepressant types out of the ten most commonly dispensed ones in children and adolescents that have indications in these age categories (Supplementary Table 6). In children, 10.0% of the dispensed prescriptions pertained to drugs that are off-label in that age category, while the figure was 18.9% in adolescents in 2013 (Supplementary Table 3).

Patterns of antidepressant prescription

Table 2 shows the patterns of dispensed antidepressant prescriptions in 2013 by type of antidepressant, source of prescription, and duration of treatment, stratified by sex and age group. Overall, there were similar patterns of use between the sexes. For both males and females, SSRIs were the single most prevalent antidepressant type. Other antidepressants were the second most common antidepressant type across ages, except among 0- to 11-year-old females, where TCAs held this spot. Mirtazapine and bupropion were common “other” antidepressants, accounting for 8.7% and 1.7% of all dispensed antidepressant prescriptions. The proportion of antidepressant users with a dispensed prescription for an SNRI or other antidepressant was the highest for young adults. Finally, 13.5% (n = 7969) of antidepressant users across age groups collected more than one type of antidepressant drug in 2013.

A majority of individuals dispensing antidepressant prescriptions in the 0- to 11-year and 12- to 17-year age groups received their prescriptions from psychiatric care (above 70%), with non-psychiatric specialist care as the second most common source except in female adolescents. In young adults, 52.7% of males and 48.2% of females received their prescriptions from psychiatric care. For all age groups and for both sexes, the majority of antidepressant users had treatment periods longer than 1 year.

Central nervous system polypharmacy

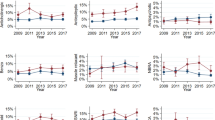

Figure 1 presents the changes in CNS polypharmacy among antidepressant users of different ages during the period 2006–2013. CNS polypharmacy of at least one additional CNS drug class increased in all age categories over the study period (from 52.4 to 62.1%)—with the biggest increase (48.8–69.9%) in the adolescent category. However, the largest increase in polypharmacy of two and three or more psychotropic drugs in addition to antidepressants was in children (from 17.4 to 28.6% and from 4.4 to 10.1%, respectively). This age category also had the highest proportion of antidepressant users with dispensed prescriptions of three or more psychotropic drugs in addition to antidepressants throughout the period.

Table 3 shows the proportion of antidepressant users who collected additional CNS drugs, alongside the ORs for receiving other CNS drugs in antidepressant users versus controls. In all age groups, anxiolytics, hypnotics, and sedatives were the most common class of drugs, with prescriptions collected by 49.8, 57.1, and 53.9% of antidepressant users in the child, adolescent, and adult populations, respectively. In the two youngest age categories, this was followed by ADHD medication (47.7% prevalence in children and 27.5% in adolescents) and antipsychotics (19.0% and 13.0%, respectively). In the 18- to 24-year-olds, antipsychotics was the second largest group (13.2%), followed by opioids (12.6%). Individuals collecting antidepressant prescriptions were more likely to use other CNS drugs than population controls. Anxiolytics, hypnotics, and sedatives had the highest OR of being dispensed in antidepressant users versus controls in all age groups [OR of 64.1 (95% CI 36.4–112.7) in children, 68.0 (95% CI 58.6–78.7) in adolescents, and 44.4 (95% CI 41.8–47.1) in young adults]. This was followed by antipsychotics for all age groups.

Finally, antidepressant users presented higher proportions of psychiatric disorders as compared to population controls (Supplementary Table 5). Out of all the common psychiatric disorders considered, child antidepressant users had the highest ORs of having an anxiety disorder diagnosis, as compared to population controls. For adolescents and young adults, antidepressant users had the highest ORs of a depression diagnosis, compared to population controls.

Discussion

In this population-based study of antidepressant dispensations among young individuals in Sweden, we found a number of noteworthy patterns over the study period (2006–2013). First, the dispensation of antidepressant drugs increased across all age categories, with the greatest relative increase in adolescents. Second, most individuals collected prescriptions for SSRIs, received their prescriptions from psychiatric specialist care, and had treatment periods of over 12 months. Third, there was extensive co-medication with other CNS drugs; the proportion of individuals collecting antidepressants at the pharmacy with any level of CNS polypharmacy rose from 52.4% in 2006 to 62.1% in 2013. To our knowledge, this is the first nationwide study showing the growth in CNS polypharmacy over this period and in this age group.

The prevalence of antidepressant dispensation increased in all age categories over the study period, with the 12- to 17-year age group seeing the greatest percentage rise (by 97.8% in males and 86.3% in females). A similar rise in antidepressant use has been documented among the young in many Western settings over the last decade—including in Dutch, British, American, Danish, and German populations over the period 2005–2012 [8]. By contrast, in a French study, the prevalence of antidepressant use rose only marginally among those aged 6–17 years (from 0.51 to 0.53%), and fell in the 6- to 11-year-olds, during 2009–2016 [32]. On the one hand, the increase documented in our study may be warranted by higher rates of diagnosed mood and anxiety disorders in the population. For example, a US-based study found that major depressive episodes among adolescents and young adults increased over the period 2005–2014 [7]; and is the source for the evidence presented in the sentence “evidence from Sweden indicates that the proportion of individuals aged 16–24 who self-reported mental ill-health more than tripled between 1988–1989 and 2004–2005 [33]; and that there was a marked increase in the proportion of individuals seeking care for psychiatric problems among the young in 2000–2014 in Stockholm [34]. On the other hand, there is a debate about whether antidepressants are efficacious treatment alternatives in this age group, and whether they have acceptable trade-offs between benefits and harms [35]. In particular, studies suggest an increased risk of suicidality and aggression in antidepressant users under age 25 years [13, 36–38], meaning that the rise of antidepressant dispensation in this age group should be monitored closely. Consistent with findings that the onset of most major mood and anxiety disorders occurs in adolescence or early adulthood [39], there was a higher prevalence of having dispensed one or more antidepressant prescriptions with increasing age over the study period. We also observed that antidepressant use was about two times more prevalent among women compared to men in adolescents and young adults, which is a pattern found among adults in many countries [40–45], as well as among the young in other European populations [32]. However, males had higher prevalence of antidepressant use than females in the 0- to 11-year-olds in our study, which warrants further investigation.

SSRIs constituted the most common antidepressant drug class across all age categories. This is in accordance with the current guidelines from the Swedish National Board of Health and Welfare, where SSRIs are recommended as the first-line pharmacological treatment for mood and anxiety disorders across ages [46]. However, SSRIs were somewhat less common in young adults compared to the younger age groups. This may be the result of SSRIs being the recommended first-line pharmacological treatment for mood and anxiety disorders among children and adolescents except in treatment-resistant cases, whereas guidelines for those aged above 18 years are less restrictive [46]. The majority of individuals dispensing antidepressant prescriptions across age categories received their prescriptions from psychiatric specialist services, although there was a more even split between specialist and primary care in the 18–24-year-olds. This mirrors the situation in a German study, where a majority of antidepressant prescriptions were made by child and adolescent psychiatrists in 2011 [10]. However, in a French study, 74.6% of first antidepressant prescriptions to 6- to 17-year-olds were prescribed by general practitioners in 2016 [32]. Across all age groups, the majority of antidepressant users were dispensed antidepressants for more than 1 year, although young adults presented somewhat higher proportions of single dispensed prescriptions than children and adolescents. The proportion of antidepressant users collecting single prescriptions is quite low compared to a study based on German insurance claims data (46.4% of users during 2004–2011) [10]. However, a study of antidepressant prescription in adult populations across five European countries found that the prevalence of SSRI users with one prescription ranged between 13% and 37% in 2008 [42]—a span that encompasses the prevalence of single dispensed prescriptions in young adults in our study. Our study also considers prescriptions dispensed at a pharmacy, a number that is expected to be lower than prescriptions made by a health-care provider. In 2013, 13.5% of antidepressant users dispensed prescriptions for more than one type of antidepressant drug, although this number did not distinguish between concurrent use and “switching” between medication types. A majority of antidepressant prescriptions are part of long-term antidepressant treatment in a number of Western settings [44, 47, 48]. Previous clinical guidelines have mainly focused on treatment initiation and appropriate targeting of antidepressants—research and guidelines on long-term use of antidepressants have been called for [47].

CNS drug polypharmacy with antidepressants increased across age categories during 2006–2013. The youngest group experienced the greatest increase in CNS polypharmacy over the study period, and this was also the age group with the highest proportion of antidepressant users receiving drugs from three or more additional CNS drug classes. A previous study from the USA has found an increase in the prevalence of CNS polypharmacy among 6- to 17-year-old antidepressant users during the period 1996–2007 [21], although more recent studies of this kind are lacking. A trend of increasing CNS polypharmacy warrants attention, as there is a lack of evidence regarding the risk and efficacy of combining CNS drugs in this age group [36]. However, polypharmacy is challenging to address. There is a lack of clarity concerning what is the appropriate treatment of multi-morbidity, and what is overprescription with potentially harmful outcomes [17]. Clinicians often lack direction in this area, as guidelines generally focus on one or a cluster of disorders rather than polypharmacy specifically [49]. Further efforts to improve monitoring of antidepressant use and CNS polypharmacy are necessary [50, 51].

Finally, we also found that antidepressant users were more likely than population controls to use a range of other CNS drugs in 2013. Anxiolytics, hypnotics, and sedatives comprised the most commonly dispensed drug class in conjunction with antidepressants. There were somewhat different co-medication patterns across age groups, partly reflecting distinct proportions of psychiatric diagnoses by age. It is noteworthy that the ORs of receiving other CNS medication concurrently with antidepressants were higher in those under the age of 17 years than in young adults. This may indicate that child and adolescent antidepressant users comprise a more selected clinical group with complex and heterogeneous symptoms that antidepressants alone do not sufficiently address—or that health-care providers mainly prescribe antidepressants in the most severe cases in this age group.

The key strength of this study is that it draws on a nationwide sample of all individuals living in Sweden. This allowed us to assess subgroup-specific patterns in a non-selected sample, giving unique insight into the rise of CNS polypharmacy among young antidepressant users from a complete population cohort. Some limitations should also be considered. First, we used dispensed antidepressant prescriptions as proxies for use, but cannot be sure that the purchased medications were consumed. However, this is closer to the final user than prescription data alone. Second, we did not have information on the indications for antidepressant prescriptions, or on diagnoses that were made in primary care. Finally, these results derive from Sweden and so are not necessarily generalizable to other contexts. While we see stability in demographic patterns of antidepressant prescription across national contexts, further studies are needed to assess whether the clinical patterns are replicated in other countries.

To conclude—in our nationwide sample, we have found several patterns of antidepressant dispensation among children, adolescents, and young adults that require further investigation. The high degree of CNS polypharmacy is a potential cause for concern, as is the rise in antidepressant dispensation generally. These findings highlight the need for studies on the risks and benefits of antidepressants among young users, to inform future research and guideline development.

References

World Health Organization (2017) Depression and other common mental disorders: global health estimates. World Health Organization, Geneva

Steel Z, Marnane C, Iranpour C, Chey T, Jackson JW, Patel V, Silove D (2014) The global prevalence of common mental disorders: a systematic review and meta-analysis 1980–2013. Int J Epidemiol 43(2):476–493

Castaneda AE, Tuulio-Henriksson A, Marttunen M, Suvisaari J, Lönnqvist J (2008) A review on cognitive impairments in depressive and anxiety disorders with a focus on young adults. J Affect Disord 106(1–2):1–27

Rapaport MH, Clary C, Fayyad R, Endicott J (2005) Quality-of-life impairment in depressive and anxiety disorders. Am J Psychiatry 162(6):1171–1178

Fröjd SA, Nissinen ES, Pelkonen MU, Marttunen MJ, Koivisto A-M, Kaltiala-Heino R (2008) Depression and school performance in middle adolescent boys and girls. J Adolesc 31(4):485–498

Thapar A, Collishaw S, Pine DS, Thapar AK (2012) Depression in adolescence. Lancet 379(9820):1056–1067

Mojtabai R, Olfson M, Han B (2016) National trends in the prevalence and treatment of depression in adolescents and young adults. Pediatrics 138(6):e20161878

Bachmann CJ, Aagaard L, Burcu M, Glaeske G, Kalverdijk LJ, Petersen I, Schuiling-Veninga CC, Wijlaars L, Zito JM, Hoffmann F (2016) Trends and patterns of antidepressant use in children and adolescents from five western countries, 2005-2012. Eur Neuropsychopharmacol 26(3):411–419. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.euroneuro.2016.02.001

Sarginson J, Webb RT, Stocks SJ, Esmail A, Garg S, Ashcroft DM (2017) Temporal trends in antidepressant prescribing to children in UK primary care, 2000–2015. J Affect Disord 210:312–318

Schröder C, Dörks M, Kollhorst B, Blenk T, Dittmann RW, Garbe E, Riedel O (2017) Outpatient antidepressant drug use in children and adolescents in Germany between 2004 and 2011. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf 26(2):170–179

Whittington CJ, Kendall T, Fonagy P, Cottrell D, Cotgrove A, Boddington E (2004) Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors in childhood depression: systematic review of published versus unpublished data. Lancet 363(9418):1341–1345

Breggin PR (2004) Suicidality, violence and mania caused by selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs): a review and analysis. Int J Risk Saf Med 16(1):31–49

Sharma T, Guski LS, Freund N, Gøtzsche PC (2016) Suicidality and aggression during antidepressant treatment: systematic review and meta-analyses based on clinical study reports. BMJ 352:i65

Friedman RA (2014) Antidepressants’ black-box warning—10 years later. N Engl J Med 371(18):1666–1668

Schneeweiss S, Patrick AR, Solomon DH, Dormuth CR, Miller M, Mehta J, Lee JC, Wang PS (2010) Comparative safety of antidepressant agents for children and adolescents regarding suicidal acts. Pediatrics 125(5):876–888

Lu CY, Zhang F, Lakoma MD, Madden JM, Rusinak D, Penfold RB, Simon G, Ahmedani BK, Clarke G, Hunkeler EM (2014) Changes in antidepressant use by young people and suicidal behavior after FDA warnings and media coverage: quasi-experimental study. BMJ 348:g3596

Sirois C, Tannenbaum C, Gagnon M-E, Milhomme D, Émond V (2016) Monitoring polypharmacy at the population level entails complex decisions: results of a survey of experts in geriatrics and pharmacotherapy. Drugs Ther Perspect 32(6):257–264

Sarkar S (2017) Psychiatric polypharmacy, etiology and potential consequences. current. Psychopharmacology 6(1):12–26

Hilt RJ, Chaudhari M, Bell JF, Wolf C, Koprowicz K, King BH (2014) Side effects from use of one or more psychiatric medications in a population-based sample of children and adolescents. J Child Adolesc Psychopharmacol 24(2):83–89

Schröder C, Dörks M, Kollhorst B, Blenk T, Dittmann RW, Garbe E, Riedel O (2017) Extent and risks of antidepressant off-label use in children and adolescents in Germany between 2004 and 2011. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf 26(11):1395–1402

Comer JS, Olfson M, Mojtabai R (2010) National trends in child and adolescent psychotropic polypharmacy in office-based practice, 1996-2007. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 49(10):1001–1010

Ludvigsson JF, Otterblad-Olausson P, Pettersson BU, Ekbom A (2009) The Swedish personal identity number: possibilities and pitfalls in healthcare and medical research. Eur J Epidemiol 24(11):659–667

Wettermark B, Hammar N, MichaelFored C, Leimanis A, Otterblad Olausson P, Bergman U, Persson I, Sundström A, Westerholm B, Rosén M (2007) The new Swedish Prescribed Drug Register—opportunities for pharmacoepidemiological research and experience from the first six months. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf 16(7):726–735

Furu K, Wettermark B, Andersen M, Martikainen JE, Almarsdottir AB, Sørensen HT (2010) The Nordic countries as a cohort for pharmacoepidemiological research. Basic Clin Pharmacol Toxicol 106(2):86–94

Ludvigsson JF, Andersson E, Ekbom A, Feychting M, Kim J-L, Reuterwall C, Heurgren M, Olausson PO (2011) External review and validation of the Swedish national inpatient register. BMC Public Health 11(1):450

Fazel S, Wolf A, Chang Z, Larsson H, Goodwin GM, Lichtenstein P (2015) Depression and violence: a Swedish population study. Lancet Psychiatry 2(3):224–232

Sellgren C, Landén M, Lichtenstein P, Hultman C, Långström N (2011) Validity of bipolar disorder hospital discharge diagnoses: file review and multiple register linkage in Sweden. Acta Psychiatr Scand 124(6):447–453

Ekholm B, Ekholm A, Adolfsson R, Vares M, Ösby U, Sedvall GC, Jönsson EG (2005) Evaluation of diagnostic procedures in Swedish patients with schizophrenia and related psychoses. Nord J Psychiatry 59(6):457–464

Ludvigsson JF, Almqvist C, Bonamy A-KE, Ljung R, Michaëlsson K, Neovius M, Stephansson O, Ye W (2016) Registers of the Swedish total population and their use in medical research. Eur J Epidemiol 31(2):125–136

Olfson M, Marcus SC (2009) National patterns in antidepressant medication treatment. Arch Gen Psychiatry 66(8):848–856. https://doi.org/10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2009.81

Pearce N (2016) Analysis of matched case-control studies. BMJ 352:i969

Revet A, Montastruc F, Raynaud J-P, Baricault B, Montastruc J-L, Lapeyre-Mestre M (2018) Trends and patterns of antidepressant use in French children and adolescents from 2009 to 2016: a population-based study in the French health insurance database. J Clin Psychopharmacol 38(4):327–335

Lager A, Berlin M, Heimerson I, Danielsson M (2012) Young people’s health: health in Sweden: the national public health report 2012. Chapter 3. Scand J Public Health 40(9 Suppl):42–71

Stockholm County Council (2016) Vilka diagnoser står för ökningen av unga vuxnas vårdkonsumtion för psykiatriska tillstånd? Faktablad 2016:1

Cipriani A, Zhou X, Del Giovane C, Hetrick SE, Qin B, Whittington C, Coghill D, Zhang Y, Hazell P, Leucht S (2016) Comparative efficacy and tolerability of antidepressants for major depressive disorder in children and adolescents: a network meta-analysis. Lancet 388(10047):881–890

Gordon MS, Melvin GA (2014) Do antidepressants make children and adolescents suicidal? J Paediatr Child Health 50(11):847–854

US Food and Drug Administration (2007) FDA proposes new warnings about suicidal thinking, behavior in young adults who take antidepressant medications. US Food and Drug Administration, Silver Spring ([Online] May 2)

Molero Y, Lichtenstein P, Zetterqvist J, Gumpert CH, Fazel S (2015) Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors and violent crime: a cohort study. PLoS Med 12(9):e1001875

McGorry PD, Purcell R, Goldstone S, Amminger GP (2011) Age of onset and timing of treatment for mental and substance use disorders: implications for preventive intervention strategies and models of care. Curr Opin Psychiatry 24(4):301–306

Sundell KA, Gissler M, Petzold M, Waern M (2011) Antidepressant utilization patterns and mortality in Swedish men and women aged 20-34 years. Eur J Clin Pharmacol 67(2):169–178. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00228-010-0933-z

Kuo CL, Chien IC, Lin CH, Cheng SW (2015) Trends, correlates, and disease patterns of antidepressant use among elderly persons in Taiwan. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol 50(9):1407–1415. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00127-015-1052-z

Abbing-Karahagopian V, Huerta C, Souverein PC, de Abajo F, Leufkens HG, Slattery J, Alvarez Y, Miret M, Gil M, Oliva B, Hesse U, Requena G, de Vries F, Rottenkolber M, Schmiedl S, Reynolds R, Schlienger RG, de Groot MC, Klungel OH, van Staa TP, van Dijk L, Egberts AC, Gardarsdottir H, De Bruin ML (2014) Antidepressant prescribing in five European countries: application of common definitions to assess the prevalence, clinical observations, and methodological implications. Eur J Clin Pharmacol 70(7):849–857. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00228-014-1676-z

Aarts N, Noordam R, Hofman A, Tiemeier H, Stricker BH, Visser LE (2014) Utilization patterns of antidepressants between 1991 and 2011 in a population-based cohort of middle-aged and elderly. Eur Psychiatry 29(6):365–370. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eurpsy.2014.02.001

Noordam R, Aarts N, Verhamme KM, Sturkenboom MC, Stricker BH, Visser LE (2015) Prescription and indication trends of antidepressant drugs in the Netherlands between 1996 and 2012: a dynamic population-based study. Eur J Clin Pharmacol 71(3):369–375. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00228-014-1803-x

Zhong W, Kremers HM, Yawn BP, Bobo WV, St Sauver JL, Ebbert JO, Finney Rutten LJ, Jacobson DJ, Brue SM, Rocca WA (2014) Time trends of antidepressant drug prescriptions in men versus women in a geographically defined US population. Arch Women’s Mental Health 17(6):485–492. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00737-014-0450-7

Swedish Medical Products Agency (2016) Depression, ångestsyndrom och tvångssyndrom hos barn och vuxna—behandlingsrekommendation. Information från Läkemedelsverket 27(6):26–59

Moore M, Yuen HM, Dunn N, Mullee MA, Maskell J, Kendrick T (2009) Explaining the rise in antidepressant prescribing: a descriptive study using the general practice research database. BMJ 339:b3999. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.b3999

Pratt LA, Brody DJ, Gu Q (2011) Antidepressant use in persons aged 12 and over: United States, 2005–2008. NCHS Data Brief 76:1–8

Payne RA (2016) The epidemiology of polypharmacy. Clin Med 16(5):465–469

Von Korff M, Goldberg D (2001) Improving outcomes in depression: the whole process of care needs to be enhanced. BMJ: Br Med J 323(7319):948

Archer J, Bower P, Gilbody S, Lovell K, Richards D, Gask L, Dickens C, Coventry P (2012) Collaborative care for depression and anxiety problems. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 10:Cd006525. https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.CD006525.pub2

Funding

There was no direct funding specific to this project. This work was supported by the Swedish Research Council for Health, Working Life and Welfare (2014-2780), Loo and Hans Osterman Foundation for Medical Research, Stockholm County Council, and the Swedish Research Council through the Swedish Initiative for Research on Microdata in the Social and Medical Sciences (SIMSAM) framework Grant no 340-2013-5867. The sponsors had no role in the planning, execution, or interpretation of this study.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics

The study was approved by the Regional Ethics Committee, Stockholm, Sweden (reference number 2013/862-31/5). The requirement for informed consent was waived because the study was register based and the included individuals were not identifiable at any time.

Conflict of interest

All authors declare no support from any organization for the submitted work. Dr. Fernández de la Cruz receives royalties for contributing articles to UpToDate, Wolters Kluwer Health, unrelated to this work; Prof. Mataix-Cols receives royalties for contributing articles to UpToDate, Wolters Kluwer Health, and fees for editorial work from Elsevier, unrelated to this work. All other authors declare no financial relationships with any organizations that might have an interest in the submitted work in the previous 3 years.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

OpenAccess This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Lagerberg, T., Molero, Y., D’Onofrio, B.M. et al. Antidepressant prescription patterns and CNS polypharmacy with antidepressants among children, adolescents, and young adults: a population-based study in Sweden. Eur Child Adolesc Psychiatry 28, 1137–1145 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00787-018-01269-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00787-018-01269-2