Abstract

The human sense of smell is still much underappreciated, despite its importance for vital functions such as warning and protection from environmental hazards, eating behavior and nutrition, and social communication. We here approach olfaction as a sense of well-being and review the available literature on how the sense of smell contributes to building and maintaining well-being through supporting nutrition and social relationships. Humans seem to be able to extract nutritional information from olfactory food cues, which can trigger specific appetite and direct food choice, but may not always impact actual intake behavior. Beyond food enjoyment, as part of quality of life, smell has the ability to transfer and regulate emotional conditions, and thus impacts social relationships, at various stages across life (e.g., prenatal and postnatal, during puberty, for partner selection and in sickness). A better understanding of how olfactory information is processed and employed for these functions so vital for well-being may be used to reduce potential negative consequences.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Among the different human sensory modalities, the sense of smell is one of the least explored, and much of its functions have yet to be clarified. This gap in our knowledge has been supported by decades of repeated attitude of laymen and scientists alike, who considered—and sometimes still consider—the sense of smell as an intuitive, yet not particularly telling source of information for humans. But, we have now collected sufficient information to disprove this prejudice (McGann 2017), and the COVID-19 pandemic has shown us full force the limits of fueling these outdated theories (Parma et al. 2020; Pellegrino et al. 2020; Cooper et al. 2020; Gerkin et al. 2020; Pierron et al. 2020). Yet, olfaction is still a sense that is not strongly associated with the idea of well-being in the general population. Whereas impairments of sight or hearing are screened for routinely since an early age to detect issues that may impact quality of life, this is not the case for olfactory disorders that still go massively unnoticed. As a result, olfaction becomes important to well-being when smell loss and/or smell alterations appear, and they are very much treated not only as an invisible disability but one that is hard to even conceive of. Up to 49% percent of people report over their lifetime an olfactory disorder, with anosmia accounting for 5% of the population (Landis et al. 2004; Murphy 2002; Mullol et al. 2012). All in all, millions of people during their lifetimes suffer from olfactory disorders, and as a consequence, report a negative impact on mental and emotional health, increased social isolation, and associated financial difficulties related to receiving the support they need, which often consists of non-curative solutions (Neuland et al. 2011; Croy et al. 2014; Erskine and Philpott 2020). These patients often report to have issues in their ability to protect themselves from environmental hazards, in their food enjoyment and eating behavior, and in their social relationships, all scenarios linked to the main functions of the sense of smell (Stevenson 2010).

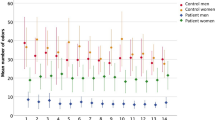

A wealth of research both in the domain of common and of social odors has focused on danger detection and the role of the sense of smell in fostering the preservation of the human species (Parma et al. 2017a; Parma et al. 2017b). In the present chapter, we focus our attention on the more understudied perspective of olfaction as a sense for well-being. Based on our experience with patients with smell loss, and their significantly reduced quality of life as a result of their disorder (Neuland et al. 2011; Erskine and Philpott 2020; Croy et al. 2014), we will review how the sense of smell critically contributes to building and maintaining well-being (Fig. 1). Although the third major function of olfaction—related to avoidance and protection from environmental hazards —clearly contributes to human well-being, this function has been reviewed in previous work (Parma et al. 2017a). Here we choose to focus on functions with more positive connotation and emphasize how olfaction supports nutrition and social relationships.

Schematic representation of the three olfactory functions described by Stevenson (2010) with a focus on how olfaction promotes well-being through nutrition and social behavior, with an outline of the topics reviewed in the chapter

Nutrition

Odors are part of the flavor percept during food consumption (retronasal) (McCrickerd and Forde 2016; Small 2012), but more importantly, even before ingestion, odors can alert us to food in our environment and orient our appetite (McCrickerd and Forde 2016; Boesveldt and Graaf 2017). Just imagine walking past a bakery in the morning, and sensing the smell of freshly-baked bread. A sudden sensation of appetite is triggered, and that may result in the irresistible urge to treat yourself. On the other hand, when you have a cold, and your nose is blocked, food does not taste so good anymore and lacks enjoyment, because the olfactory component is missing. In addition, early exposure to flavors in breast milk or formula, or even exposure in utero, can shape food preferences later in life (Beauchamp and Mennella 2011). These olfactory signals are crucial behavioral drivers in our food-abundant environment, and it is imperative to better understand the underlying mechanisms, and under what conditions they act, in order to steer people towards better eating patterns.

Olfaction, similarly to vision, can be considered a so-called distant sense. In the presence of food, olfactory signals can be perceived before consumption, and may stimulate appetite in anticipation of food intake. Several studies have now clearly demonstrated that odors trigger appetite specifically for the cued product (Fedoroff et al. 2003; Morquecho-Campos et al. 2020; Ramaekers et al. 2014; Zoon et al. 2016), a phenomenon coined sensory-specific appetite. In addition, this effect may generalize to other foods with similar characteristics. For instance, after exposure to a meat odor, the specific appetite for meat increases most, but also stimulates appetite for other savory products, such as curry. Moreover, this sensory-specific appetite is not only present for odors and foods that share similar sensory characteristics (i.e., taste category, such as sweet, savory) (Ramaekers et al. 2014), but also odors representing high- or low-energy-dense foods specifically induce appetite for (same and other) food products high or low in energy density (Zoon et al 2016). Interestingly, we have recently shown that humans, like other species, can use their olfactory sense in their foraging or eating behavior strategies, i.e., to navigate for (high-calorie) food in different environments (de Vries et al. 2020). It is thus likely that, similar to taste being a nutrient sensing system, food odors can signal information about the nutrient composition of their associated foods already before ingestion. This would be based on learned associations, due to repeated combined exposure to an odor and the post-ingestive consequences of the food throughout life (Brunstrom and Mitchell 2007; Small et al. 2008; Yeomans and Boakes 2016; Yeomans et al. 2016). This information may trigger cephalic phase responses—a myriad of physiological responses (e.g., saliva, hormones, digestive enzymes), to help the body start preparing for the ingestion and digestion of that specific food/macronutrient (Smeets et al. 2010; Morquecho-Campos et al. 2020). For a detailed review of the relation between olfaction and appetite hormones, see Palouzier-Paulignan et al. (2012).

Even though subjective ratings of appetite have predictive value for food intake (de Graaf et al. 2004), they cannot be directly extrapolated; i.e., people do not always eat what they want or when they are hungry, and they also do not always refrain from eating when satiated (Drapeau et al. 2007; Mattes et al. 1990; Stubbs et al. 2000; Parker et al. 2004). Hitherto, beyond appetite, reports on the effect of olfactory cues on more tangible measures of eating behavior, such as food choices, and intake, are conflicting. These inconsistent results may be grounded in methodological differences between study designs. For instance, in a series of studies, Gaillet and colleagues have shown that starters and desserts containing fruit and vegetables were selected more frequently from a menu upon unconscious exposure to melon and pear odor, respectively (Gaillet et al. 2013; Gaillet-Torrent et al. 2014). Others have similarly shown a positive influence of unaware odor exposure on subsequent congruent food choices (de Wijk and Zijlstra 2012; Chambaron et al. 2015), while awareness of the odor did not result in similar food choices (Zoon et al. 2014). As much decision making occurs at a non-conscious level (Köster 2009), this suggests that olfactory effects on food choice may operate through priming, and the odor needs to be unattended or presented subthreshold in order to exert its influences (Smeets and Dijksterhuis 2014). The relationship between odor exposure and subsequent intake is also not straightforward. Fedoroff et al. observed an increase in intake after odor exposure only for restrained eaters (Fedoroff et al. 2003), whereas Coelho et al. found that restrained eaters decreased their food intake upon odor exposure (Coelho et al. 2009). On the other hand, Larsen and colleagues and Proserpio et al. observed an increase in intake for low impulse eaters only (Larsen et al 2012), or upon unconscious odor exposure (Proserpio et al. 2017; Porserpio et al. 2019). Finally, several studies did not find any differences in intake after (conscious) exposure to odors signaling foods differing in macronutrient content or energy–density (Morquecho-Campos et al. 2020; Zoon et al. 2014).

Impact of smell loss on eating behavior

Most of the studies above have focused on short-term effects of experimental interventions to study the influence of olfaction on eating behavior. If our sense of smell indeed plays an important role in the dietary choices we make in our daily lives, this may exert longer-term effects, such as changes in body weight or body mass index (BMI). Additionally, patients that experience olfactory dysfunction (e.g., elderly, anosmics; although olfactory loss can occur for a plethora of reasons (Temmel et al. 2002) may show differences in their food preferences and intake, and such findings will provide further insight into the importance of smell for nutritional behavior.

Though most studies have indicated that a decreased sense of smell is related to poor appetite, lower interest in food-related activities, or decreased food enjoyment (Aschenbrenner et al. 2008; Jong et al. 1999; Duffy et al. 1995; Philpott and Boak 2014; Postma et al. 2020), the impact on dietary patterns or overall diet quality appears to be less consistent (Mattes et al. 1990; Aschenbrenner et al. 2008; Duffy et al. 1995; Postma et al. 2020; Gopinath et al. 2016), and may depend on the duration of olfactory loss (i.e., being it acquired throughout life or congenital and thus present from birth). Moreover, patients with smell loss typically do not have lower energy intake or present with low BMI (Mattes et al. 1990; de Jong et al. 1999; Duffy et al. 1995). In addition, research has shown no relation between (loss of) olfactory function and liking of (flavor-enhanced) foods (Kremer et al. 2007, 2014; Koskinen et al. 2003; Boesveldt et al. 2018). Thus, although there may not be a direct relation between olfactory function and nutritional status (Toussaint et al. 2015), smell loss mostly affects the pleasure in food behavior. Moreover, eating can be considered as social behavior (e.g., enjoying family dinners, going out to a restaurant with friends, or cooking for your loved-ones), and it is indeed known that olfactory loss is associated with depressive symptoms (Croy et al. 2014), as the absence of smell can have more general impact on quality of life and well-being (Philpott and Boak 2014; Boesveldt et al. 2017).

Social behavior

The sense of smell represents a significant medium to transfer information that is critical to foster relationships among co-specifics (Lübke and Pause 2015; Semin and de Groot 2013), as well as inter-species (Semin et al. 2019). Possibly due to its evolutionary role in creating and maintaining sociality, sweat-based olfactory communication is effortless—we spontaneously sweat and breathe—and we are among the most odoriferous hominidis species (Stoddart 1990). Indeed, despite most research on human sweat being confined to the axillary area (Mitro et al. 2012; Pause et al. 1998; Mutic et al. 2016; Chen and Havilandjones 1999; Ferdenzi et al. 2009; Cecchetto et al. 2019; Doty et al. 1978; Dalton et al. 2013; Sorokowska et al. 2016; Smeets et al. 2020; de Groot et al. 2018; Rocha et al. 2018), many areas of the body are able to produce and transfer chemosignals (e.g., eyes through tears (Gelstein et al. 2011), hands (Frumin et al. 2015), increasing the potential for chemosensory communication. Furthermore, sweat-based olfactory communication is resistant to perturbation from the restrictions imposed by physical and time barriers, since chemical molecules can freely disperse in air and water (Zelano and Sobel 2005). It therefore remains efficient when senses that humans typically rely on are unavailable (e.g., in the dark, in loud environments), even when chemosensory noise is present (Roberts 2012). Indeed, chemosensory communication is not blocked by the use of fragrances, a widespread custom across societies (Saxton et al. 2008).

The processing of information decoded from sweat represents a form of honest communication (Martín and López 2008), which does not require conscious awareness (Lundström and Olsson 2010) and is applied to a variety of human relational contexts. These features make communication based on chemicals possible across developmental stages, from intrauterine life (Beauchamp and Mennella 2011) to the elderly (Prokop-Prigge et al. 2016), and available to the fraction of the population affected by cognitive and social impairments (Parma et al. 2013). By simply reviewing the type of information that sweat-based olfactory communication successfully conveys, it is clear that one of its main functions is the fostering of stable relationships: sweat chemically encodes personal identity (Schleidt et al. 1981; Platek et al. 2001), kin and relatives (Lundström et al. 2009; Porter et al. 1986), partner choice (Schleidt et al. 1981; Lundström and Jones-Gotman 2009), and more broadly, friendship (Lundström et al. 2009). Additionally, sweat can also chemically encode health status (Moshkin et al. 2012; Olsson et al. 2014), sexual availability (Gildersleeve et al. 2012), and emotional states (fear, de Groot and Smeets 2017; disgust, Zheng et al. 2018; aggression/competition, Mutic et al. 2016; sadness, Oh et al. 2012; happiness, de Groot et al. 2015), factors that regulate the more transient aspects of relationships.

The role of smell in relationships follows mankind across developmental stages

Odors start to become a form of social communication as early as in utero, and it further strengthens postnatally when the odorous secretions of the areola attract the newborn and facilitate latching and breastfeeding (Doucet et al. 2012), while mothers’ attachment to their baby is also reinforced through a chemosensory channel (Lundström et al. 2013). In infancy, the maternal odor is used to regulate the infant’s emotional processing (Jessen 2020) and disambiguates the visual environment e.g., faces (Leleu et al. 2020). During childhood, children tend to like and be comforted by their mother’s odors (Ferdenzi et al. 2010), whereas same-sex parental odors become aversive during pubertal age, contributing to the discouragement of incestuous relationships Westermarck effect (Schäfer et al. 2020). Despite a renaissance of the investigation of body odor processing in childhood in the most recent years (Schäfer et al. 2020), this area of research is rather understudied.

Instead, a wealth of evidence has been collected on the role of body odors in attraction and mate choice. Many studies reveal that preferences for the body odors that signal the quality of a partner in terms of compatibility, with a preference for the odors of people having a dissimilar HLA (Havlicek and Roberts 2009), and for the odor of people having a compatible sexual orientation (Martins et al. 2005). Additionally, men prefer the smell of women while they are in the fertile phase of their menstrual cycle (Singh and Bronstad 2001; Havlíček et al. 2006), an effect that fades away when women use contraceptives (Kuukasjarvi 2004). All in all, body odors, along with other sensory cues, shape physical attractiveness and promote (or not) mating (Miller and Todd 1998).

Smell-triggered emotion regulation

More broadly, sweat-based information is used to transfer information about well-being via transferring happiness (de Groot et al. 2015) or a lack thereof (Mutic et al. 2016; de Groot and Smeets 2017; Zheng et al. 2018; Oh et al. 2012). Human sweat produces behavioral, psychophysiological, and neurophysiological consequences in recipients in line with the emotional condition at encoding. In a communication perspective (Smeets et al. 2017), human sweat collected in emotional situations stimulates partial synchronization between donors and recipients, in line with the concept of emotional contagion (Hatfield et al. 1993). In other words, affective, behavioral, and perceptual processes observed in a receiver following exposure to human sweat constitute in many cases a partial reproduction of the state of the donor at the time of body odor production. Specific experiences, such as pregnancy, reduce the effectiveness of sweat-based emotional communication, such as in the case of reduced responses to anxiety sweat signals to protect the mother and the fetus from the adverse consequences of stress reactions (Lübke et al. 2017). Though emotional contagion is a widespread mechanism regulating sweat communication, it is not the only one. Individuals can respond not only by mimicking the sweat donor’s experience but also by providing complementary responses to it, such as when "smelling aggression" is met with heightened anxiety (Mutic et al. 2016).

These mechanisms are particularly interesting when at play to promote personal well-being, and social attuning. In the specific case of autism spectrum disorder, a pathology that is keenly characterized by lack or reduction in social competence, smelling the odor of a familiar person, with whom interaction is positive, has the great advantage of letting emerge functional behaviors such as automatic imitation (Parma et al. 2013, 2014). By leveraging the power of odors to modulate breathing patterns (Arshamian et al. 2018), individuals with autism can be offered a low-effort opportunity of emotional regulation. It is well known by now that regulating breathing patterns, whether voluntarily or not, has a calming effect (Zaccaro et al. 2018).

Impact of smell loss on relationships

The impact that smell loss has on relationships is strong, simply imaging failing to detect one’s own bad body odor and how this will immediately affect the people in the vicinity. Taking this negative outcome a step forward, smell loss can affect sexual relationships and mate choice in people, especially for those with congenital anosmia (Philpott and Boak 2014; Croy et al. 2013; Schäfer et al. 2019). Having no or reduced ability in reading the social world through the lens of olfaction can severely affect attachment, limit the ability to “read a room,” and the strategies used to initiate emotional regulation, associated with the experience of having an invisible illness. These phenomena are not only limited to early development and adulthood, but span continuously over the lifespan, including the elderly population. Indeed, it is believed that the association between olfactory performance and the richness of social connectedness could reflect social modulation processes occurring in aging (Boesveldt et al. 2017), which are known variables influencing health outcomes in this segment of the population.

General conclusions

Overall, the evidence presented in this chapter suggests that the olfactory modality is a reliable medium through which social communication can occur among humans. By playing a critical role in nutrition and social relationships, smell is a sense that is instrumental to the achievement and maintenance of well-being. As the COVID-19 pandemic revealed, the widespread olfactory loss and dysfunction often left in the wake of a COVID-19 diagnosis, significantly trumps one’s sense of well-being, shedding light on the silent importance of the sense of smell.

From a nutrition perspective, changes in or loss of olfactory capability mostly impacts food enjoyment and can, but do not automatically, lead to changes in dietary patterns. It is clear that the relation between olfactory signals and eating behavior is complex and entails more than plain liking or wanting of food induced by odor cues. Moreover, few studies have looked at real-life situations, e.g., shopping malls and nursing homes, to investigate the effect odors may have on our daily food choices and eating patterns, or over longer periods of time.

The study of the effect of odors on social relationships has so far highlighted the pervasive role of olfaction in fostering sociality. Importantly, the majority of this evidence is collected in the absence of a real-time communicative exchange (often donors and recipients do not jointly interact). The decontextualization of the information encoded in sweat may possibly be removing part of the beneficial effects of this social behavior. What are the social dimensions in human chemosensory emotional contagion? How does sweat-based communication affect relationships and well-being outside of the laboratory? These remain at present open questions.

If we understand how and under which circumstances olfactory signals lead up to food intake, this may be used to steer (overweight) people towards healthier foods, or to enhance appetite in malnourished elderly or patients. Similarly, if we understand how social chemosensory information can be used to foster accurate social information processing and emotional regulation, this may be used to reduce the negative consequences of these inabilities. Research for the years to come, that we plan on doing and that we look forward to seeing in bulk in the literature, will aid to fully exploit the potential that olfaction offers to improve human well-being.

References

Arshamian A, Iravani B, Majid A, Lundström JN et al (2018) Respiration modulates olfactory memory consolidation in humans. J Neurosci 38:10286–10294. https://doi.org/10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3360-17.2018

Aschenbrenner K, Hummel C, Teszmer K, Krone F, Ishimaru T, Seo H-S et al (2008) The influence of olfactory loss on dietary behaviors. The Laryngoscope 118:135–144. https://doi.org/10.1097/MLG.0b013e318155a4b9

Beauchamp GK, Mennella JA (2011) Flavor perception in human infants: development and functional significance. Digestion 83:1–6. https://doi.org/10.1159/000323397

Boesveldt S, de Graaf K (2017) The differential role of smell and taste for eating behavior. Perception 46:307–319. https://doi.org/10.1177/0301006616685576

Boesveldt S, Yee JR, McClintock MK, Lundström JN et al (2017) Olfactory function and the social lives of older adults: a matter of sex. Sci Rep 7:45118. https://doi.org/10.1038/srep45118

Boesveldt S, Postma EM, Boak D, Welge-Luessen A, Schöpf V, Mainland JD et al (2017) Anosmia—a clinical review. Chem Senses 42:513–523. https://doi.org/10.1093/chemse/bjx025

Boesveldt S, Bobowski N, McCrickerd K, Maître I, Sulmont-Rossé C, Forde CG et al (2018) The changing role of the senses in food choice and food intake across the lifespan. Food Qual Prefer 68:80–89. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foodqual.2018.02.004

Brunstrom JM, Mitchell GL (2007) Flavor–nutrient learning in restrained and unrestrained eaters. Physiol Behav 90:133–141. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.physbeh.2006.09.016

Cecchetto C, Lancini E, Bueti D, Rumiati RI, Parma V et al (2019) Body odors (even when masked) make you more emotional: behavioral and neural insights. Sci Rep 9:5489. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-019-41937-0

Chambaron S, Chisin Q, Chabanet C, Issanchou S, Brand G et al (2015) Impact of olfactory and auditory priming on the attraction to foods with high energy density. Appetite 95:74–80. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.appet.2015.06.012

Chen D, Havilandjones J (1999) Rapid mood change and human odors. Physiol Behav 68:241–250. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0031-9384(99)00147-X

Coelho JS, Polivy J, Peter Herman C, Pliner P et al (2009) Wake up and smell the cookies. Effects of olfactory food-cue exposure in restrained and unrestrained eaters. Appetite 52:517–520. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.appet.2008.10.008

Cooper KW, Brann DH, Farruggia MC, Bhutani S, Pellegrino R, Tsukahara T et al (2020) COVID-19 and the chemical senses: supporting players take center stage. Neuron 107:219–233. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neuron.2020.06.032

Croy I, Bojanowski V, Hummel T et al (2013) Men without a sense of smell exhibit a strongly reduced number of sexual relationships, women exhibit reduced partnership security—a reanalysis of previously published data. Biol Psychol 92:292–294. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biopsycho.2012.11.008

Croy I, Nordin S, Hummel T et al (2014) Olfactory disorders and quality of life–an updated review. Chem Senses 39:185–194. https://doi.org/10.1093/chemse/bjt072

Croy I, Symmank A, Schellong J, Hummel C, Gerber J, Joraschky P et al (2014) Olfaction as a marker for depression in humans. J Affect Disord 160:80–86. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2013.12.026

Dalton P, Mauté C, Jaén C, Wilson T et al (2013) Chemosignals of stress influence social judgments. PLoS ONE 8:e77144. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0077144

de Graaf C, Blom WA, Smeets PA, Stafleu A, Hendriks HF et al (2004) Biomarkers of satiation and satiety. Am J Clin Nutr 79:946–961. https://doi.org/10.1093/ajcn/79.6.946

de Groot JHB, Smeets MAM (2017) Human fear chemosignaling: evidence from a meta-analysis. Chem Senses 42:663–673. https://doi.org/10.1093/chemse/bjx049

de Groot JHB, Smeets MAM, Rowson MJ, Bulsing PJ, Blonk CG, Wilkinson JE et al (2015) A sniff of happiness. Psychol Sci 26:684–700. https://doi.org/10.1177/0956797614566318

de Groot JHB, van Houtum LAEM, Gortemaker I, Ye Y, Chen W, Zhou W et al (2018) Beyond the west: chemosignaling of emotions transcends ethno-cultural boundaries. Psychoneuroendocrinology 98:177–185. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psyneuen.2018.08.005

de Jong N, Mulder I, de Graaf C, van Staveren WA et al (1999) Impaired sensory functioning in elders: the relation with its potential determinants and nutritional intake. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci 54:B324–B331. https://doi.org/10.1093/gerona/54.8.B324

Smeets JHB, de G Gün R Semin, Monique AM et al (2017) On the communicative function of body odors: a theoretical integration and review - Jasper H. B. de Groot, Gün R. Semin, Monique A. M. Smeets, 2017. Perspect Psychol Sci

de Vries R, de Vet E, de Graaf K, Boesveldt S et al (2020) Foraging minds in modern environments: high-calorie and savory-taste biases in human food spatial memory. Appetite 152:104718. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.appet.2020.104718

de Wijk RA, Zijlstra SM (2012) Differential effects of exposure to ambient vanilla and citrus aromas on mood, arousal and food choice. Flavour 1:24. https://doi.org/10.1186/2044-7248-1-24

Doty RL, Orndorff MM, Leyden J, Kligman A et al (1978) Communication of gender from human axillary odors: relationship to perceived intensity and hedonicity. Behav Biol 23:373–380. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0091-6773(78)91393-7

Doucet S, Soussignan R, Sagot P, Schaal B et al (2012) An overlooked aspect of the human breast: areolar glands in relation with breastfeeding pattern, neonatal weight gain, and the dynamics of lactation. Early Hum Dev 88:119–128. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.earlhumdev.2011.07.020

Drapeau V, King N, Hetherington M, Doucet E, Blundell J, Tremblay A et al (2007) Appetite sensations and satiety quotient: predictors of energy intake and weight loss. Appetite 48:159–166. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.appet.2006.08.002

Duffy VB, Backstrand JR, Ferris AM et al (1995) Olfactory dysfunction and related nutritional risk in free-living Elderly Women. J Am Diet Assoc 95:879–884. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0002-8223(95)00244-8

Erskine SE, Philpott CM (2020) An unmet need: Patients with smell and taste disorders. Clin Otolaryngol 45:197–203. https://doi.org/10.1111/coa.13484

Fedoroff I, Polivy J, Peter HC et al (2003) The specificity of restrained versus unrestrained eaters’ responses to food cues: general desire to eat, or craving for the cued food? Appetite 41:7–13. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0195-6663(03)00026-6

Ferdenzi C, Schaal B, Roberts SC et al (2009) Human axillary odor: are there side-related perceptual differences? Chem Senses 34:565–571. https://doi.org/10.1093/chemse/bjp037

Ferdenzi C, Schaal B, Roberts SC et al (2010) Family scents: developmental changes in the perception of kin body odor? J Chem Ecol 36:847–854. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10886-010-9827-x

Frumin I, Perl O, Endevelt-Shapira Y, Eisen A, Eshel N, Heller I et al (2015) A social chemosignaling function for human handshaking. ELife 4:e05154. https://doi.org/10.7554/eLife.05154

Gaillet M, Sulmont-Rossé C, Issanchou S, Chabanet C, Chambaron S et al (2013) Priming effects of an olfactory food cue on subsequent food-related behaviour. Food Qual Prefer 30:274–281. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foodqual.2013.06.008

Gaillet-Torrent M, Sulmont-Rossé C, Issanchou S, Chabanet C, Chambaron S et al (2014) Impact of a non-attentively perceived odour on subsequent food choices. Appetite 76:17–22. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.appet.2014.01.009

Gelstein S, Yeshurun Y, Rozenkrantz L, Shushan S, Frumin I, Roth Y et al (2011) Human tears contain a chemosignal. Science 331:226–230

Gerkin RC, Ohla K, Veldhuizen MG, Joseph PV, Kelly CE, Bakke AJ et al (2020) Recent smell loss is the best predictor of COVID-19: a preregistered, cross-sectional study. MedRxiv. https://doi.org/10.1101/2020.07.22.20157263

Gildersleeve KA, Haselton MG, Larson CM, Pillsworth EG et al (2012) Body odor attractiveness as a cue of impending ovulation in women: evidence from a study using hormone-confirmed ovulation. Horm Behav 61:157–166. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.yhbeh.2011.11.005

Gopinath B, Russell J, Sue CM, Flood VM, Burlutsky G, Mitchell P et al (2016) Olfactory impairment in older adults is associated with poorer diet quality over 5 years. Eur J Nutr 55:1081–1087. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00394-015-0921-2

Hatfield E, Cacioppo JT, Rapson RL et al (1993) Emotional contagion. Curr Dir Psychol Sci 2:96–100. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-8721.ep10770953

Havlíček J, Dvořáková R, Bartoš L, Flegr J et al (2006) Non-advertized does not mean concealed: body odour changes across the human menstrual cycle. Ethology 112:81–90. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1439-0310.2006.01125.x

Havlicek J, Roberts SC (2009) MHC-correlated mate choice in humans: a review. Psychoneuroendocrinology 34:497–512. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psyneuen.2008.10.007

Jessen S (2020) Maternal odor reduces the neural response to fearful faces in human infants. Dev Cogn Neurosci 45:100858. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.dcn.2020.100858

Koskinen S, Kälviäinen N, Tuorila H et al (2003) Flavor enhancement as a tool for increasing pleasantness and intake of a snack product among the elderly. Appetite 41:87–96. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0195-6663(03)00054-0

Köster EP (2009) Diversity in the determinants of food choice: a psychological perspective. Food Qual Prefer 20:70–82. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foodqual.2007.11.002

Kremer S, Bult JHF, Mojet J, Kroeze JHA et al (2007) Compensation for age-associated chemosensory losses and its effect on the pleasantness of a custard dessert and a tomato drink. Appetite 48:96–103. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.appet.2006.08.001

Kremer S, Holthuysen N, Boesveldt S et al (2014) The influence of olfactory impairment in vital, independently living older persons on their eating behaviour and food liking. Food Qual Prefer 38:30–39. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foodqual.2014.05.012

Kuukasjarvi S (2004) Attractiveness of women’s body odors over the menstrual cycle: the role of oral contraceptives and receiver sex. Behav Ecol 15:579–584. https://doi.org/10.1093/beheco/arh050

Landis BN, Konnerth CG, Hummel T et al (2004) A Study on the Frequency of Olfactory Dysfunction. The Laryngoscope 114:1764–1769. https://doi.org/10.1097/00005537-200410000-00017

Larsen JK, Hermans RCJ, Engels RCME et al (2012) Food intake in response to food-cue exposure. Examining the influence of duration of the cue exposure and trait impulsivity. Appetite 58:907–913. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.appet.2012.02.004

Leleu A, Rekow D, Poncet F, Schaal B, Durand K, Rossion B et al (2020) Maternal odor shapes rapid face categorization in the infant brain. Dev Sci 23:e12877. https://doi.org/10.1111/desc.12877

Lübke KT, Pause BM (2015) Always follow your nose: the functional significance of social chemosignals in human reproduction and survival. Horm Behav 68:134–144. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.yhbeh.2014.10.001

Lübke KT, Busch A, Hoenen M, Schaal B, Pause BM et al (2017) Pregnancy reduces the perception of anxiety. Sci Rep 7:9213. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-017-07985-0

Lundström JN, Jones-Gotman M (2009) Romantic love modulates women’s identification of men’s body odors. Horm Behav 55:280–284. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.yhbeh.2008.11.009

Lundström JN, Olsson MJ Functional neuronal processing of human body odors. Vitam Horm, vol. 83. Elsevier; 2010. p. 1–23

Lundström JN, Boyle JA, Zatorre RJ, Jones-Gotman M et al (2009) The neuronal substrates of human olfactory based kin recognition. Hum Brain Mapp 30:2571–2580. https://doi.org/10.1002/hbm.20686

Lundström JN, Mathe A, Schaal B, Frasnelli J, Nitzsche K, Gerber J et al (2013) Maternal status regulates cortical responses to the body odor of newborns. Front Psychol 4:597. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2013.00597

Martín J, López P (2008) Female sensory bias may allow honest chemical signaling by male Iberian rock lizards. Behav Ecol Sociobiol 62:1927–1934. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00265-008-0624-2

Martins Y, Preti G, Crabtree CR, Runyan T, Vainius AA, Wysocki CJ et al (2005) Preference for human body odors is influenced by gender and sexual orientation. Psychol Sci 16:694–701. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9280.2005.01598.x

Mattes RD, Cowart BJ, Schiavo MA, Arnold C, Garrison B, Kare MR et al (1990) Dietary evaluation of patients with smell and/or taste disorders. Am J Clin Nutr 51:233–240. https://doi.org/10.1093/ajcn/51.2.233

McCrickerd K, Forde CG (2016) Sensory influences on food intake control: moving beyond palatability. Obes Rev 17:18–29. https://doi.org/10.1111/obr.12340

McGann JP (2017) Poor human olfaction is a 19th-century myth. Science 356 https://doi.org/10.1126/science.aam7263

Miller GF, Todd PM (1998) Mate choice turns cognitive. Trends Cogn Sci 2:190–198. https://doi.org/10.1016/s1364-6613(98)01169-3

Mitro S, Gordon AR, Olsson MJ, Lundström JN et al (2012) The smell of age: perception and discrimination of body odors of different ages. PLoS ONE 7:e38110. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0038110

Morquecho-Campos P, de Graaf K, Boesveldt S et al (2020) Smelling our appetite? The influence of food odors on congruent appetite, food preferences and intake. Food Qual Prefer 85:103959. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foodqual.2020.103959

Morquecho-Campos P, Bikker FJ, Nazmi K, de Graaf K, Laine ML, Boesveldt S et al (2020) A stepwise approach investigating salivary responses upon multisensory food cues. Physiol Behav 226:113116. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.physbeh.2020.113116

Moshkin M, Litvinova N, Litvinova EA, Bedareva A, Lutsyuk A, Gerlinskaya L et al (2012) Scent recognition of infected status in humans. J Sex Med 9:3211–3218. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1743-6109.2011.02562.x

Mullol J, Alobid I, Mariño-Sánchez F, Quintó L, de Haro J, Bernal-Sprekelsen M et al (2012) Furthering the understanding of olfaction, prevalence of loss of smell and risk factors: a population-based survey (OLFACAT study). BMJ Open 2:e001256. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2012-001256

Murphy C (2002) Prevalence of olfactory impairment in older adults. JAMA 288:2307. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.288.18.2307

Mutic S, Parma V, Brünner YF, Freiherr J et al (2016) You smell dangerous: communicating fight responses through human chemosignals of aggression. Chem Senses 41:35–43. https://doi.org/10.1093/chemse/bjv058

Neuland C, Bitter T, Marschner H, Gudziol H, Guntinas-Lichius O et al (2011) Health-related and specific olfaction-related quality of life in patients with chronic functional anosmia or severe hyposmia. The Laryngoscope 121:867–872. https://doi.org/10.1002/lary.21387

Oh TJ, Kim MY, Park KS, Cho YM et al (2012) Effects of chemosignals from sad tears and postprandial plasma on appetite and food intake in humans. PLoS ONE 7:e42352. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0042352

Olsson MJ, Lundström JN, Kimball BA, Gordon AR, Karshikoff B, Hosseini N et al (2014) The scent of disease: human body odor contains an early chemosensory cue of sickness. Psychol Sci 25:817–823. https://doi.org/10.1177/0956797613515681

Palouzier-Paulignan B, Lacroix M-C, Aimé P, Baly C, Caillol M, Congar P et al (2012) Olfaction under metabolic influences. Chem Senses 37:769–797. https://doi.org/10.1093/chemse/bjs059

Parker BA, Sturm K, MacIntosh CG, Feinle C, Horowitz M, Chapman IM et al (2004) Relation between food intake and visual analogue scale ratings of appetite and other sensations in healthy older and young subjects. Eur J Clin Nutr 58:212–218. https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.ejcn.1601768

Parma V, Bulgheroni M, Tirindelli R, Castiello U et al (2013) Body odors promote automatic imitation in autism. Biol Psychiatry 74:220–226. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biopsych.2013.01.010

Parma V, Bulgheroni M, Tirindelli R, Castiello U et al (2014) Facilitation of action planning in children with autism: the contribution of the maternal body odor. Brain Cogn 88:73–82. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bandc.2014.05.002

Parma V, Wilson D, Lundström JN et al (2017) Aversive olfactory conditioning. In: Buettner A, editor. Springer Handb. Odor. Cham: Springer International Publishing. p. 103–4

Parma V, Gordon AR, Cecchetto C, Cavazzana A, Lundström JN, Olsson MJ et al (2017) Processing of human body odors. In: Buettner A, editor. Springer Handb. Odor. Cham: Springer International Publishing. p. 127–8

Parma V, Ohla K, Veldhuizen MG, Niv MY, Kelly CE, Bakke AJ et al (2020) More than smell – COVID-19 is associated with severe impairment of smell, taste, and chemesthesis. Chem Senses(Epub ahead of print): https://doi.org/10.1093/chemse/bjaa041

Pause BM, Krauel K, Sojka B, Ferstl R et al (1998) Body odor evoked potentials: a new method to study the chemosensory perception of self and non-self in humans. Genetica 104:285–294. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1026462701154

Pellegrino R, Cooper KW, Di Pizio A, Joseph PV, Bhutani S, Parma V et al (2020) Corona viruses and the chemical senses: past, present, and future. Chem Senses. https://doi.org/10.1093/chemse/bjaa031

Philpott CM, Boak D (2014) The impact of olfactory disorders in the United Kingdom. Chem Senses 39:711–718. https://doi.org/10.1093/chemse/bju043

Pierron D, Pereda-Loth V, Mantel M, Moranges M, Bignon E, Alva O et al (2020) Self-reported smell and taste changes are early indicators of the COVID-19 pandemic and of the effectiveness of political decisions. Nat Commun n.d.;accepted

Platek SM, Burch RL, Gallup GG et al (2001) Sex differences in olfactory self-recognition. Physiol Behav 73:635–640. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0031-9384(01)00539-X

Porter RH, Balogh RD, Cernoch JM, Franchi C et al (1986) Recognition of kin through characteristic body odors. Chem Senses 11:389–395. https://doi.org/10.1093/chemse/11.3.389

Postma EM, De Graaf C, Boesveldt S et al (2020) Food preferences and intake in a population of Dutch individuals with self-reported smell loss: an online survey. Food Qual Prefer 79:103771. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foodqual.2019.103771

Prokop-Prigge KA, Greene K, Varallo L, Wysocki CJ, Preti G et al (2016) The Effect of Ethnicity on Human Axillary Odorant Production. J Chem Ecol 42:33–39. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10886-015-0657-8

Proserpio C, de Graaf C, Laureati M, Pagliarini E, Boesveldt S et al (2017) Impact of ambient odors on food intake, saliva production and appetite ratings. Physiol Behav 174:35–41. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.physbeh.2017.02.042

Proserpio C, Invitti C, Boesveldt S, Pasqualinotto L, Laureati M, Cattaneo C et al (2019) Ambient odor exposure affects food intake and sensory specific appetite in obese women. Front Psychol 10:7. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2019.00007

Ramaekers MG, Boesveldt S, Lakemond CMM, van Boekel MAJS, Luning PA et al (2014) Odors: appetizing or satiating? Development of appetite during odor exposure over time. Int J Obes 38:650–656. https://doi.org/10.1038/ijo.2013.143

Roberts SC (2012) Applied Evolutionary Psychology. OUP Oxford

Rocha M, Parma V, Lundström JN, Soares SC et al (2018) Anxiety body odors as context for dynamic faces: categorization and psychophysiological biases. Perception 47:1054–1069. https://doi.org/10.1177/0301006618797227

Saxton T, Lyndon A, Little A, Roberts S et al (2008) Evidence that androstadienone, a putative human chemosignal, modulates women’s attributions of men’s attractiveness. Horm Behav 54:597–601. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.yhbeh.2008.06.001

Schäfer L, Mehler L, Hähner A, Walliczek U, Hummel T, Croy I et al (2019) Sexual desire after olfactory loss: quantitative and qualitative reports of patients with smell disorders. Physiol Behav 201:64–69. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.physbeh.2018.12.020

Schäfer L, Sorokowska A, Sauter J, Schmidt AH, Croy I et al (2020) Body odours as a chemosignal in the mother–child relationship: new insights based on an human leucocyte antigen-genotyped family cohort. Philos Trans R Soc B Biol Sci 375:20190266. https://doi.org/10.1098/rstb.2019.0266

Schäfer L, Sorokowska A, Weidner K, Croy I et al (2020) Children’s body odors: hints to the development status. Front Psychol 11:320. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2020.00320

Schleidt M, Hold B, Attili G et al (1981) A cross-cultural study on the attitude towards personal odors. J Chem Ecol 7:19–31. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF00988632

Semin GR, de Groot JHB (2013) The chemical bases of human sociality. Trends Cogn Sci 17:427–429. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tics.2013.05.008

Semin GR, Scandurra A, Baragli P, Lanatà A, D’Aniello B et al (2019) Inter- and intra-species communication of emotion: chemosignals as the neglected medium. Animals 9:887. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani9110887

Singh D, Bronstad PM (2001) Female body odour is a potential cue to ovulation. Proc Biol Sci 268:797–801. https://doi.org/10.1098/rspb.2001.1589

Small DM (2012) Flavor is in the brain. Physiol Behav 107:540–552. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.physbeh.2012.04.011

Small DM, Veldhuizen MG, Felsted J, Mak YE, McGlone F et al (2008) Separable substrates for anticipatory and consummatory food chemosensation. Neuron 57:786–797. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neuron.2008.01.021

Smeets MA, Dijksterhuis GB (2014) Smelly primes—when olfactory primes do or do not work. Front Psychol 5:96. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2014.00096

Smeets PA, Erkner A, Graaf CD et al (2010) Cephalic phase responses and appetite. Nutr Rev 68:643–655. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1753-4887.2010.00334.x

Smeets MAM, Rosing EAE, Jacobs DM, van Velzen E, Koek JH, Blonk C et al (2020) Chemical fingerprints of emotional body odor. Metabolites 10:84. https://doi.org/10.3390/metabo10030084

Sorokowska A, Sorokowski P, Havlíček J et al (2016) Body odor based personality judgments: the effect of fragranced cosmetics. Front Psychol 7:530. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2016.00530

Stevenson RJ (2010) An initial evaluation of the functions of human olfaction. Chem Senses 35:3–20. https://doi.org/10.1093/chemse/bjp083

Stoddart DM (1990) The scented ape: the biology and culture of human odour. Cambridge University Press

Stubbs RJ, Hughes DA, Johnstone AM, Rowley E, Reid C, Elia M et al (2000) The use of visual analogue scales to assess motivation to eat in human subjects: a review of their reliability and validity with an evaluation of new hand-held computerized systems for temporal tracking of appetite ratings. Br J Nutr 84:405–415. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0007114500001719

Temmel AFP, Quint C, Schickinger-Fischer B, Klimek L, Stoller E, Hummel T et al (2002) Characteristics of olfactory disorders in relation to major causes of olfactory loss. Arch Otolaryngol Neck Surg 128:635–641. https://doi.org/10.1001/archotol.128.6.635

Toussaint N, de Roon M, van Campen JPCM, Kremer S, Boesveldt S et al (2015) Loss of olfactory function and nutritional status in vital older adults and geriatric patients. Chem Senses 40:197–203. https://doi.org/10.1093/chemse/bju113

Yeomans MR, Boakes S (2016) That smells filling: effects of pairings of odours with sweetness and thickness on odour perception and expected satiety. Food Qual Prefer 54:128–136. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foodqual.2016.07.010

Yeomans MR, Re R, Wickham M, Lundholm H, Chambers L et al (2016) Beyond expectations: the physiological basis of sensory enhancement of satiety. Int J Obes 40:1693–1698. https://doi.org/10.1038/ijo.2016.112

Zaccaro A, Piarulli A, Laurino M, Garbella E, Menicucci D, Neri B et al (2018) How breath-control can change your life: a systematic review on psycho-physiological correlates of slow breathing. Front Hum Neurosci 12:353. https://doi.org/10.3389/fnhum.2018.00353

Zelano C, Sobel N (2005) Humans as an animal model for systems-level organization of olfaction. Neuron 48:431–454. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neuron.2005.10.009

Zheng Y, You Y, Farias AR, Simon J, Semin GR, Smeets MA et al (2018) Human chemosignals of disgust facilitate food judgment. Sci Rep 8:17006. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-018-35132-w

Zoon HFA, He W, de Wijk RA, de Graaf C, Boesveldt S et al (2014) Food preference and intake in response to ambient odours in overweight and normal-weight females. Physiol Behav 133:190–196. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.physbeh.2014.05.026

Zoon H, de Graaf C, Boesveldt S et al (2016) Food Odours Direct Specific Appetite. Foods 5:12. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods5010012

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding authors

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Boesveldt, S., Parma, V. The importance of the olfactory system in human well-being, through nutrition and social behavior. Cell Tissue Res 383, 559–567 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00441-020-03367-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00441-020-03367-7