Intended for healthcare professionals

CCBYNC Open access

Rapid response to:

Research

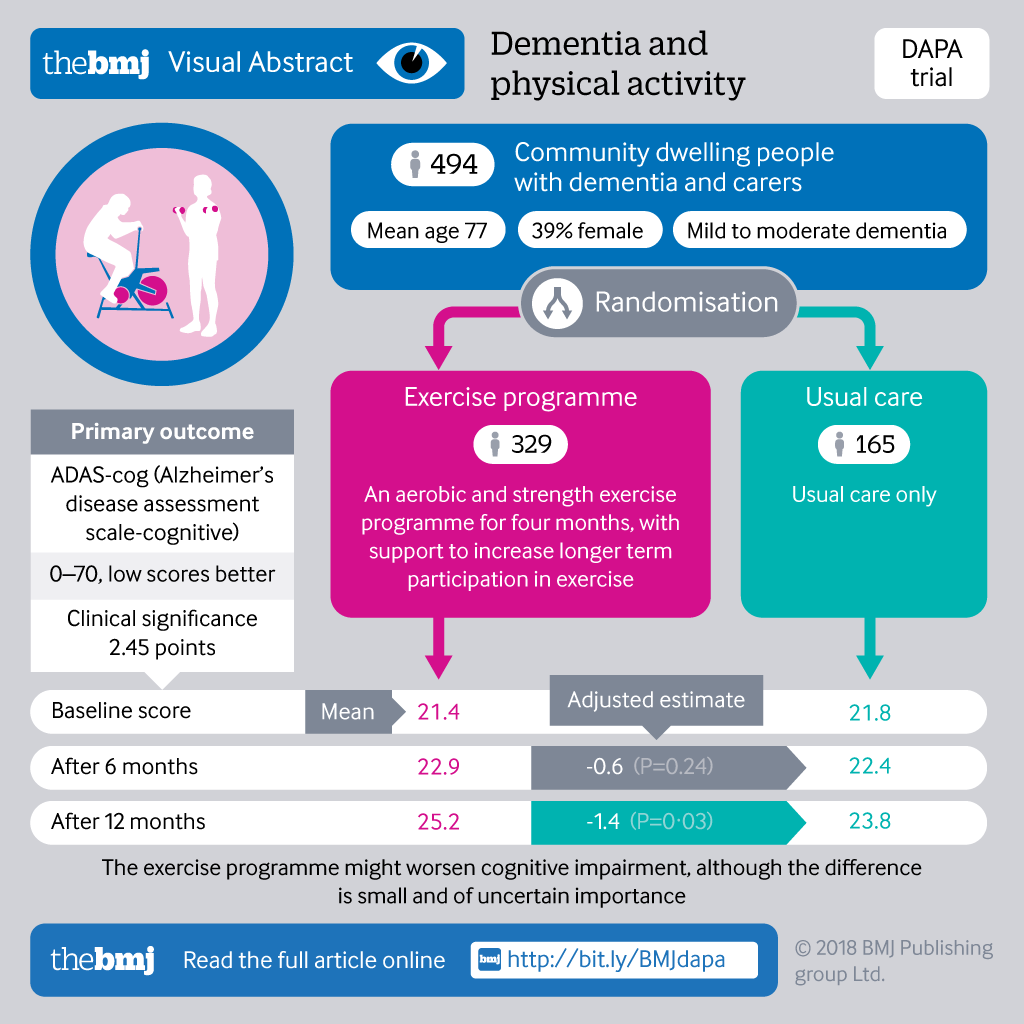

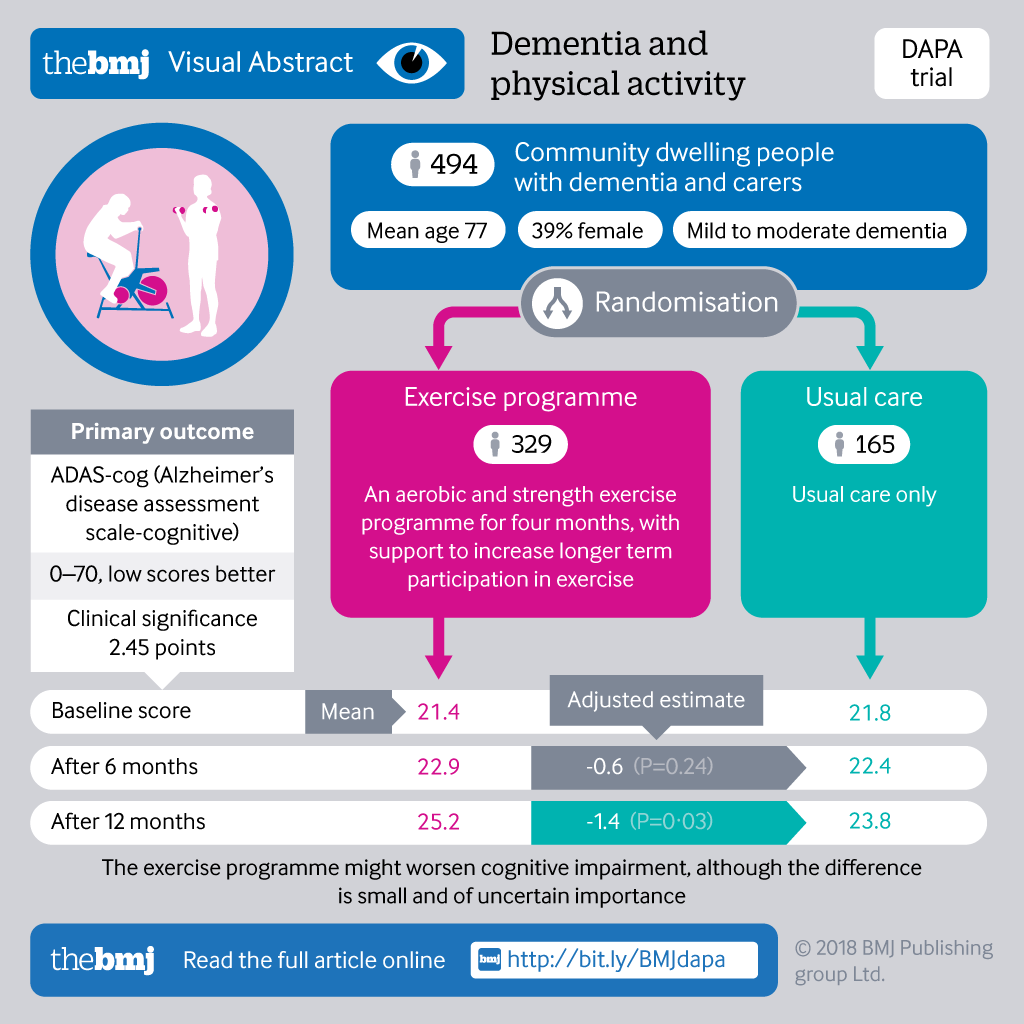

Dementia And Physical Activity (DAPA) trial of moderate to high intensity exercise training for people with dementia: randomised controlled trial

BMJ 2018; 361 doi: https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.k1675 (Published 16 May 2018) Cite this as: BMJ 2018;361:k1675

Rapid Response:

Re: Dementia And Physical Activity (DAPA) trial of moderate to high intensity exercise training for people with dementia: randomised controlled trial

Dear Editor,

Low-intensity walking in the sunshine may benefit dementia

We have been deeply impressed by the negative results of the Dementia And Physical Activity (DAPA) trial (1), which found that “the exercise programme might worsen cognitive impairment”, although the authors claimed that “the difference is small and of uncertain importance”. We do consider these findings to be of major clinical importance, although the results seem to be not in agreement with the widely held belief that exercise is beneficial to dementia.

Some might argue that the DAPA patients did not exercise with enough volume/intensity, but we would suggest low-intensity exercise for people with dementia. We have tested the effectiveness of low-intensity walking (80-90 steps/min, 2.5-3 km/h, <3 metabolic equivalents) in prehypertensive and hypertensive subjects for pressure control (2, 3). We infer that the DAPA subjects may have similar cardiovascular condition to hypertensive subjects, and if low-intensity walking benefits hypertension, it may benefit dementia as well. With increased blood flow and vasodilation, low-intensity regular walking may improve long-term cerebral blood supply and thus overall brain function.

Low-intensity outdoor walking was accompanied by β-endorphin elevation (2, 3), which we recently found out to be related to walking in the sunshine (4). We have reported the case of a 65-year-old hypertensive patient who, after regular walking during sunny winter days, had markedly ameliorated anxiety, insomnia, diabetes, along with optimal pressure control and elevated β-endorphin (3). Beta-endorphin is renowned for its gentle vasodilation and tranquilization, which could increase cerebral blood supply with simultaneous well-being. More importantly, β-endorphin is found to have neurogenesis property and be involved in exercise-induced hippocampal proliferation (5, 6), which are valuable for neurodegenerative disease.

What happens when the sun touches us with its broad spectrum of electromagnetic waves? Convincing evidence shows that our skin has is endowed with the capability of producing a plethora of neurotransmitters and hormones upon stimulation (7). Keratinocytes and melanocytes from epidermis, the external layer of our skin originated from ectoderm as central nervous system, could synthesize β-endorphin and nitric oxide when exposed to blue light and ultraviolet radiation (7-9). Notably, peripherally administrated β-endorphin and skin-derived β-endorphin were found to affect brain function in vivo (9). Therefore, with powerful solar energy, the sun may act on our skin to exert both peripheral and central effects. Beta-endorphin induced by sunlight exposure might also promote adherence to walking activities, which would further promote these locally produced peptides/neurotransmitters into circulation for target tissues including the brain.

Additionally, Alzheimer disease is closely associated with higher inflammation, and low-intensity exercise could suppress inflammatory cytokines and increase anti-inflammatory cytokines (10). Low-intensity daily walking and light physical activities were also associated with higher hippocampus or total brain volume in clinical studies (11, 12). Therefore, when combined with physiological sunlight exposure, low-intensity walking may benefit dementia through various mechanisms theoretically, and have therapeutic potential as well.

One of the significant strengths of the DAPA trial is that it also provided adverse results so that we readers could reflect on the negative profile of high-intensity exercise. The four serious exercise-related events (one angina, one substantially worsening hip pain and two injurious falls) might mostly pertain to cardiovascular overburden or post-exercise hypotension frequently encountered in strenuous exercise, leading to ischemia attack. Several of our friends also experienced serious cardiovascular events during strenuous exercise, include angina, myocardial infarction, ventricular tachyarrhythmia and atrial-ventricular blockade. Our previous study showed impaired endothelial function with elevated blood pressure after long-term high volume running even in normal animals (13).

By monitoring blood pressure during low-intensity walking, we found around 5 percent increase in systolic blood pressure, a minimal and relatively safe fluctuation. This contrasts with a general 30 percent increase in blood pressure during moderate exercise. Hypertension and sympathetic activation during exercise can be more marked in older people, resulting in cardiovascular overload and ischemia. High-intensity training could also lead to transient kidney injury in young people (2). Therefore, after the evaluation of patients’ condition, if the negative responses of vigorous exercise override its benefits, one may choose low-intensity walking as an alternative therapy. With regular walking, the heart, lung and brain would be constantly, albeit slowly, remodeled to match the physiological function that are required of them, leading to gradual improvement in health and life quality of people with dementia.

In all, low-intensity walking with adequate sunlight exposure may have favored impacts on dementia through different mechanisms. It is also cost-effective and feasible for improving the life quality of both caregivers and patients, the important objectives of the DAPA trial (1, 14). Although single walking in the sunshine has only brief effects in promoting blood supply and β-endorphin production, regular walking activities may build up enough volume for the benefits of dementia as time goes by.

Yours sincerely,

Qin Lu 1*, Rui Zhang 1*, Wen-hui Zhang 2, Yan-qian Zheng 2, Ying Wang 1, Ye Mao 1, Yan-xia Pan 3, Kyosuke Yamanishi 4, Hong Chen 1

1 Department of Pharmacology and Chemical Biology, Shanghai Jiao Tong University School of Medicine, Shanghai 200025, China

2 Department of Anatomy and Physiology, Shanghai Jiao Tong University School of Medicine, Shanghai 200025, China

3 Department of Rehabilitation Therapy, College of Medical Technology and Engineering, Fujian Medical University, Fuzhou, Fujian Province 350004, China

4 Department of Neuropsychiatry, Hyogo College of Medicine, Hyogo 663-8501, Japan

*These authors contributed equally in the study.

Correspondence:

Hong Chen, MD, PhD, hchen100@shsmu.edu.cn

Wen-hui Zhang, MD, PhD, i_zhang@163.com

Kyosuke Yamanishi, MD, PhD, k-yama@hyo-med.ac.jp

Acknowledgements:

The study was supported by grants from the National Natural Science Foundation of China to H Chen (No. 30971154, 31171099), WH Zhang (No. 81373468) and YX Pan (No. 81372111). The authors acknowledge the technical assistance of YB Tang. We are especially grateful to all the volunteers who contributed to the exercise study without compensation.

Competing interests: None.

References

1. Lamb SE, Sheehan B, Atherton N, Nichols V, Collins H, Mistry D, Dosanjh S, Slowther AM, Khan I, Petrou S, Lall R; DAPA Trial Investigators. Dementia And Physical Activity (DAPA) trial of moderate to high intensity exercise training for people with dementia: randomised controlled trial. BMJ. 2018;361:k1675.

2. Wang SM, Chen YC, Lu Q, Wang J, Zhong MF, Chen H, Zhao JM, Liu YX, Zou YY, Zhou JW, Yu JX, Hou LN, Yamanishi K, Higashino H, Yamanishi H, Okamura H. Low-speed walking for three kilometers was effective to lower short-term blood pressure and heart rate with increased β-endorphin release in normotensive and hypertensive subjects. Chin J Hypertens. 2018;26(8):953–961.

3. Lu Q, Wang S, Liu YX, Chen H, Zhang R, Zhang WH, Zou YY, Zhou JW, Guo XY, Zhang Y, Huang TL, Liu YH, Zhang SQ, Yamanishi K, Yamanishi H, Higashino H, Okamura H.. Low-intensity walking as mild medication for pressure control in prehypertensive and hypertensive subjects: how far shall we wander? Acta Pharmacol Sin. 2019;40(8):1119-1126.

4. Zhang R, Chen H, Liu YX, Zhang WH, Lu Q, Yamanishi H, Yamanishi C, Yamanishi K, Qiu YL, Ye XF, Huang ZR, Zhang BY, Chen YF, Zheng YQ, Zhang YF, Guo ZZ, Dong D, Liu TX, Dai YQ, Xu MH, Hao Y, Li SZ, Cai FY, Wang RQ, Guo XY, Zhu DH, Zhang HY, Zeng ZT, Higashino H. Sunny walking counts more. Acta Pharmacol Sin. 2019;40(9):1256-1257.

5. Bolijn S, Lucassen PJ. How the Body Talks to the Brain; Peripheral Mediators of Physical Activity-Induced Proliferation in the Adult Hippocampus. Brain Plast. 2015;1(1):5-27.

6. Keohl M, Meerio P, Gonzales D, Rontal A, Turek FW, Abrous DN. Exercise-induced promotion of hippocampal cell proliferation requires beta-endorphin. FASEB J. 2008;22(7):2253-2262.

7. Slominski AT, Zmijewski MA, Skobowiat C, Zbytek B, Slominski RM, Steketee JD. Sensing the environment: Regulation of local and global homeostasis by the skin’s neuroendocrine system. Advances in Anatomy, Embryology and Cell Biology 212, DOI 10.1007/978-3-642-19683-6_1, Springer-Verlag Berlin Heidelberg, 2012.

8. Albers I, Zernickel E, Stern M, Broja M, Busch HL, Heiss C, Grotheer V, Windolf J, Suschek CV. Blue light (λ=453 nm) nitric oxide dependently induces β-endorphin production of human skin keratinocytes in-vitro and increases systemic β-endorphin levels in humans in-vivo. Free Radic Biol Med. 2019;145:78-86.

9. Fell GL, Robinson KC, Mao J, Woolf CJ, Fisher DE. Skin β-endorphin mediates addiction to UV light. Cell. 2014;157(7):1527-1534.

10. Yakeu G, Butcher L, Isa S, Webb R, Roberts AW, Thomas AW, Backx K, James PE, Morris K. Low-intensity exercise enhances expression of markers of alternative activation in circulating leukocytes: roles of PPARγ and Th2 cytokines. Atherosclerosis. 2010;212(2):668-673.

11. Varma VR, Chuang YF, Harris GC, Tan EJ, Carlson MC. Low-intensity daily walking activity is associated with hippocampal volume in older adults. Hippocampus. 2015;25(5):605-615.

12. Spartano NL, Davis-Plourde KL, Himali JJ, Andersson C, Pase MP, Maillard P, DeCarli C, Murabito JM, Beiser AS2, Vasan RS, Seshadri S. Association of Accelerometer-Measured Light-Intensity Physical Activity With Brain Volume: The Framingham Heart Study. JAMA Netw Open. 2019;2(4):e192745.

13. Sun MW, Zhong MF, Gu J, Qian FL, Gu JZ, Chen H. Effects of different levels of exercise volume on endothelium-dependent vasodilation: roles of nitric oxide synthase and heme oxygenase. Hypertens Res. 2008;31(4):805-816.

14. Khan I, Petrou S, Khan K, Mistry D, Lall R, Sheehan B, Lamb S; DAPA Trial Group. Does Structured Exercise Improve Cognitive Impairment in People with Mild to Moderate Dementia? A Cost-Effectiveness Analysis from a Confirmatory Randomised Controlled Trial: The Dementia and Physical Activity (DAPA) Trial. Pharmacoecon Open. 2019;3(2):215-227.

Competing interests: No competing interests