Key Points

-

Most oral malodour is related to diet, habits or inadequate oral hygiene.

-

However cancer and some systemic and psychogenic diseases may present with malodour

Key Points

Oral medicine

-

1

Aphthous and other common ulcers

-

2

Mouth ulcers of more serious connotation

-

3

Dry mouth and disorders of salivation

-

4

Oral malodour

-

5

Oral white patches

-

6

Oral red and hyperpigmented patches

-

7

Orofacial sensation and movement

-

8

Orofacial swellings and lumps

-

9

Oral cancer

-

10

Orofacial pain

Abstract

This series provides an overview of current thinking in the more relevant areas of oral medicine for primary care practitioners, written by the authors while they were holding the Presidencies of the European Association for Oral Medicine and the British Society for Oral Medicine, respectively. A book containing additional material will be published. The series gives the detail necessary to assist the primary dental clinical team caring for patients with oral complaints that may be seen in general dental practice. Space precludes inclusion of illustrations of uncommon or rare disorders, or discussion of disorders affecting the hard tissues. Approaching the subject mainly by the symptomatic approach — as it largely relates to the presenting complaint — was considered to be a more helpful approach for GDPs rather than taking a diagnostic category approach. The clinical aspects of the relevant disorders are discussed, including a brief overview of the aetiology, detail on the clinical features and how the diagnosis is made. Guidance on management and when to refer is also provided, along with relevant websites which offer further detail.

Similar content being viewed by others

Oral malodour

Oral malodour, or halitosis, is a common complaint in adults, though few mention it. Malodour can have a range of causes (Table 1). With oral malodour from any cause, the patient may also complain of a bad taste.

Common causes of oral malodour

Oral malodour is common on awakening (morning breath) and then often has no special significance — usually being a consequence of low salivary flow and lack of oral cleansing during sleep as well as mouthbreathing.

This rarely has any special significance, and can be readily rectified by eating, tongue brushing, and rinsing the mouth with fresh water. Hydrogen peroxide rinses may also help abolish this odour.

Oral malodour at other times is often the consequence of eating various foods such as garlic, onion or spices, foods such as cabbage, Brussel sprouts, cauliflower and radish, or of habits such as smoking, or drinking alcohol. Durian is a tropical fruit which is particularly malodourous.

The cause of malodour in such cases is usually obvious and avoidance of the offending substance is the best prevention.

Less common causes of oral malodour

Oral infections can be responsible for oral malodour. The micro—organisms implicated in oral malodour are predominantly Gram-negative anaerobes, and include:

-

Porphyromonas gingivalis

-

Prevotella intermedia

-

Fusobacterium nucleatum

-

Bacteroides (Tannerella) forsythensis and

-

Treponema denticola.

Gram-positive bacteria have also been implicated since they can denude the available glycoproteins of their sugar chains, enabling the anaerobic Gram-negative proteolytic bacteria to break down the proteins. Gram negative bacteria can produce chemicals that produce malodour, which include in many instances

-

volatile sulphur compounds (VSCs), mainly methyl mercaptan, hydrogen sulphide, and dimethyl sulphide

-

diamines (putrescine and cadaverine) and

-

short chain fatty acids (butyric, valeric and propionic).

The evidence for the implication of other micro-organisms, such as Helicobacter pylori, is scant.

The posterior area of the tongue dorsum is often the location of the microbial activity associated with bad breath. Debris, such as in patients with poor oral hygiene, or under a neglected or a poorly designed dental bridge or appliance is another cause. Any patient with oral cancer or a dry mouth can also develop oral malodour.

Defined infective processes that can cause malodour may include:

-

Periodontal infections (especially necrotising gingivitis or periodontitis)

-

Pericoronitis

-

Other types of oral infections

-

Infected extraction sockets

-

Ulcers.

Improvement of oral hygiene, prevention or treatment of infective processes, and sometimes the use of antimicrobials can usually manage this type of oral malodour.

Rare causes of oral malodour

Systemic causes of oral malodour are rare but important and range from drugs to sepsis in the respiratory tract to metabolic disorders (Table 2).

The complaint of oral malodour in the absence of malodour

The complaint of oral malodour may be made by patients who do not have it but imagine it because of psychogenic reasons. This can be a real clinical dilemma, since no evidence of oral malodour can be detected even with objective testing, and the oral malodour may then be attributable to a form of delusion or monosymptomatic hypochondriasis (self-oral malodour; halitophobia).

Other people's behaviour, or perceived behaviour, such as apparently covering the nose or averting the face, is typically misinterpreted by these patients as an indication that their breath is indeed offensive. Such patients may have latent psychosomatic illness tendencies.

Many of these patients will adopt behaviour to minimise their perceived problem, such as

-

covering the mouth when talking

-

avoiding or keeping a distance from other people

-

avoiding social situations

-

using chewing gum, mints, mouthwashes or sprays designed to reduce malodour

-

frequent toothbrushing

-

cleaning their tongue.

Thus the oral hygiene may be superb in such patients. Medical help may be required to manage these patients.

Such patients unfortunately fail to recognise their own psychological condition, never doubt they have oral malodour and thus are often reluctant to visit a psychologic specialist.

Summary

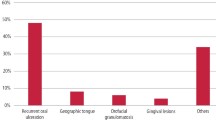

Oral malodour can have a range of causes, though most cases of true malodour have an oral cause, and many others are imagined (Fig. 1).

Diagnosis of oral malodour

Assessment of oral malodour is usually subjective by simply smelling exhaled air (organoleptic method) coming from the mouth and nose and comparing the two. Odour originating in the mouth, but not detectable from the nose is likely to be either oral or pharyngeal origin. Odour originating in the nose may come from the sinuses or nasal passages. Children sometimes place foreign bodies in the nose, leading to sepsis and malodour! Only in the rare cases in which similar odour is equally sensed coming from both the nose and mouth can one of the many systemic causes be inferred.

Specialist centres may have the apparatus for objectively measuring the responsible volatile sulphur compounds (methyl mercaptan, hydrogen sulphide, dimethyl sulphide) – a halimeter. Microbiological investigations such as the BANA (benzoyl-arginine-naphthyl-amide) test or darkfield microscopy can also be helpful.

Management of oral malodour

The management includes first determining which cases may have an extraoral aetiology.

A full oral examination is indicated and if an oral cause is likely or possible, management should include treatment of the cause, and other measures (see box).

In cases of malodour which may have an extraoral aetiology, the responsibility of the general dental practitioner is to refer the patient for evaluation to a specialist. This may involve an oral medicine opinion, an otorhinolaryngologist to rule out the presence of chronic tonsillitis or chronic sinusitis, a physician to rule out gastric, hepatic, endocrine, pulmonary, metabolic or renal disease or a psychologist or psychiatrist.

Patient information and websites

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Refereed Paper

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Scully, C., Felix, D. Oral Medicine — Update for the dental practitioner Oral malodour. Br Dent J 199, 498–500 (2005). https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.bdj.4812806

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.bdj.4812806

This article is cited by

-

Association between oral health-related quality of life and depressive symptoms in Chinese college students: Fitness Improvement Tactics in Youths (FITYou) project

Health and Quality of Life Outcomes (2019)