Gender dysphoria: assessment and management for non-specialists

BMJ 2017; 357 doi: https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.j2866 (Published 30 June 2017) Cite this as: BMJ 2017;357:j2866

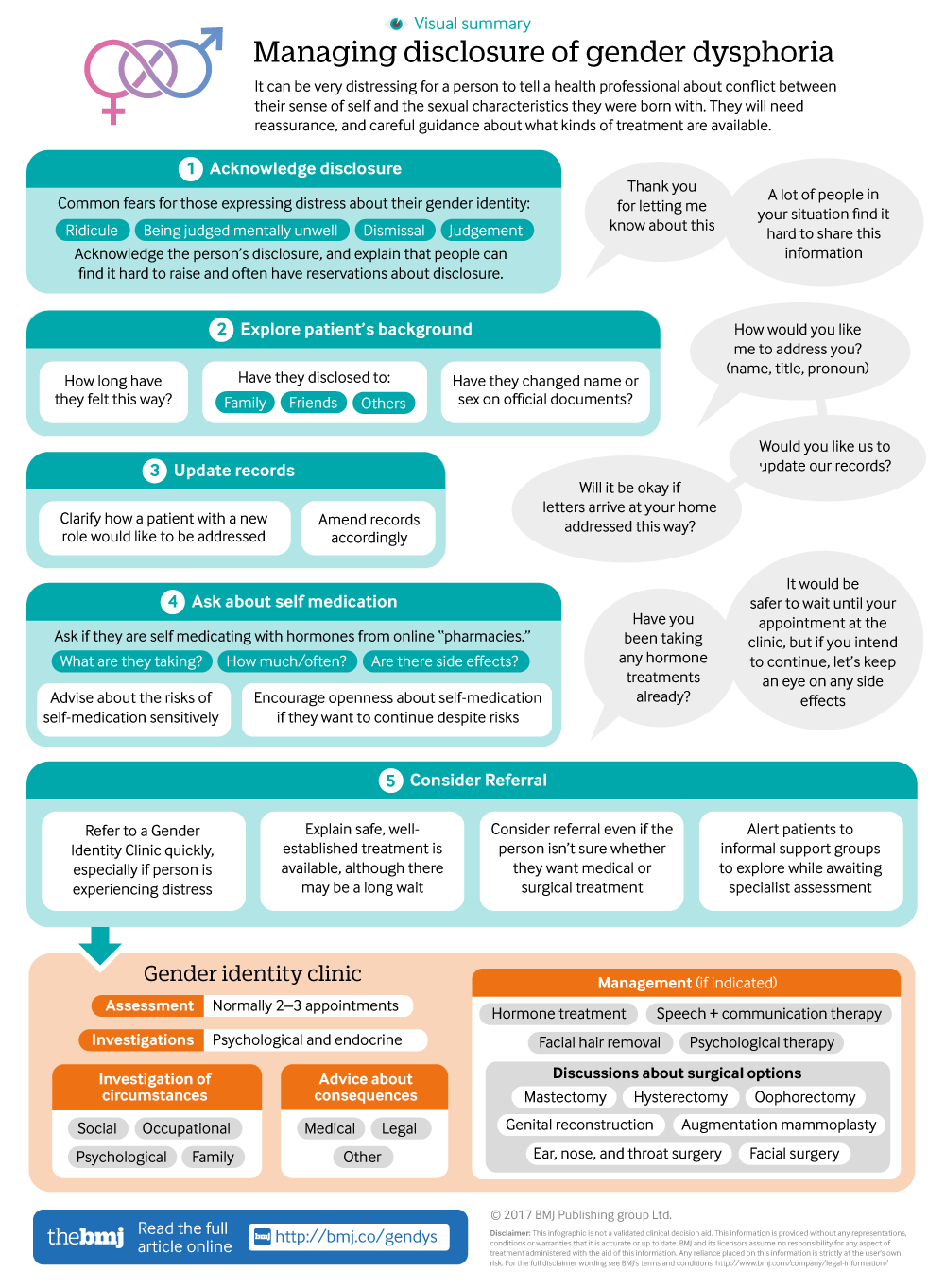

Infographic available

A visual summary of managing patients disclosing gender dysphoria, encouraging cooperation and respect to get the best experiences and outcomes for patients.

- James Barrett, lead clinician

- Correspondence to J Barrett JBarrett2{at}tavi-port.nhs.uk

- Accepted 10 May 2017

What you need to know

Refer patients with gender dysphoria directly to a multidisciplinary gender identity clinic

People in a new gender role usually need a lifelong prescription of maintenance hormone therapy, which is often provided by primary care under guidance from a gender identity clinic

A person’s earlier change of gender role is rarely clinically relevant and does not need to be mentioned unless it is

Consider birth gender when offering routine screening for cervical and breast cancer and aortic aneurysm

Clarify how a patient with a new role would like to be addressed and amend records accordingly to avoid subsequent upset

About 0.6% of the population identifies as transgender1 2 according to healthcare records, although the actual number might be higher. In the 50 years since UK NHS services started, more than 130 000 people have changed social gender role. A variety of doctors, including non-specialists, might at some time in their career be approached for help by someone with gender dysphoria.

Various specialist clinicians are involved in the care of patients being assessed and treated at a gender identity clinic. Specialist clinics obviate the need for any psychiatric assessment in advance of referral. Gender dysphoria is not a mental health disorder. After treatment is complete, doctors from all specialties will encounter patients who earlier changed gender role. People with gender dysphoria have described their experience of interacting with healthcare services as variable to poor, according to the Women and Equalities Parliamentary Select Committee.3 In the UK, the General Medical Council has recently emphasised medical duties in this regard,4,advising that treatment for transgender patients should be as respectful as for any other group. Feelings of “inexperience” with the field can prompt learning by collaboration with a gender identity clinic, rather than act as a justification for non-involvement.

This article offers guidance on how to manage an adult patient who is distressed by feelings of gender incongruence. We discuss appropriate language to use, referral processes, and options for management that are typically led by specialist teams, including hormonal, surgical, and cosmetic treatments.

The practical suggestions on how to assess and manage patients are based mainly on the experience of the authors and other members of the British Association of Gender Identity Specialists. They are also based on the few existing broad national and international guidelines on the management of transgender patients.5

What is gender dysphoria?

Gender dysphoria is a distressing sense of incongruity between individuals’ sense of themselves and the sexual characteristics they were born with. Most often there is a sense of feeling female although born male (or vice versa) but sometimes a sense of mixed gender or neutrality.

What to say, do, and explain if a patient expresses distress about their gender identity not fitting their body

Anecdotally, the biggest fears for any patient making such a disclosure are of being ridiculed, being judged as mentally unwell, or being roundly dismissed and inappropriately judged afterwards. Clinicians can allay some of those concerns by acknowledging the disclosure, and by explaining that other people in a similar position can find it hard to raise the subject, or have reservations about the implications of the disclosure.

Clinicians might begin to explore how long the patient has experienced these feelings, and what steps, if any, they have taken already to disclose to family and friends, trusted workmates, or employers. Has there been any formal name change or sex marker change on work documents or social profiles online?

Specifically, ask whether patients are self medicating with hormones from online “pharmacies” (table 1⇓). Explore this medication use as you might with any other non-prescribed drug, asking what and how much the patient is taking and how often. Screen for side effects and explain that self medication carries risks, including the loss of natural fertility. To avoid further risk, patients are advised to stop self medication until seen in a specialist clinic for further assessment. The person might not want to stop medication, especially as there can be a long wait to be seen at a gender identity clinic (typically nine to 15 months in the UK, although it is anticipated that referral to treatment times will fall to 18 weeks within the next five years). If patients are unwilling to stop self medication, encourage them to share with you any side effects they experience, and encourage them to inform healthcare staff if they are seen in other settings.

Commonly self administered drugs and associated risks

Advice differs in suggested approaches to providing ongoing prescriptions for hormonal treatments before the patient is reviewed by a gender identity clinic, and can be difficult to make a reality. The Royal College of Psychiatrists suggests that non-specialists might consider prescribing hormonal treatments while a patient is awaiting assessment by a specialist.5 The British Association of Gender Identity Specialists position statement does not recommend the practice of “bridging prescriptions” in primary care. Non-specialists might feel uncomfortable issuing such prescriptions and it is difficult for specialists to advise on how best to proceed without having assessed the person, including having screening bloods to make sure that hormone treatment is safe, and having assessed the person's psychological and social circumstances.

Explain to the patient that you will make a referral to gender services. Explain that their experience isn’t uncommon and that treatment (NHS funded treatment in the UK) is available, although sometimes associated with long waiting lists. These treatments are generally well established and safe, but should be considered on an individual basis according to the patient’s preferences.

Usually it is not necessary to inquire directly about gender dysphoria if a patient does not raise it themselves. If it is suspected, a suggestion of open mindedness about the topic might be useful. For example, you might say that you have noticed an increasing degree of masculinity or femininity in the person over time, and wonder if this reflects an increasingly authentic self expression.

When to refer to a gender clinic

Some form of treatment for gender dysphoria is available in most northern European and English speaking countries, although usually not wholly state funded. Elsewhere, availability is more patchy and of variable quality. There are few places to seek help in countries with widespread poverty or cultures hostile to people with gender dysphoria.

If gender dysphoria is distressing a patient, refer them to a gender identity clinic as swiftly as possible, as “watchful waiting” confers no benefit. Refer regardless of whether they are actively seeking medical or surgical treatment. It is useful to alert patients to informal support groups (eg, www.tranzwiki.net) that they can explore while they wait for a first assessment at a clinic. If gender dysphoria is sufficiently marked to cause low mood or deliberate self harm, a concurrent referral to local psychiatric services might be helpful. Rates of mental illness in patients treated for gender dysphoria are in line with the general population, although rates of deliberate self harm and autistic spectrum disorder are raised.6 7 8 9 If required, make a psychiatry referral concurrently with referral to a gender identity clinic.

What happens at a gender identity clinic in the UK?

Treatment at a gender identity clinic is intended to offer a safe and sustained relief of gender dysphoria and thereby improvement in quality of life. A clinic team might contain psychiatrists, psychologists, speech and language therapists, nurses, occupational therapists, counsellors, endocrinologists, general physicians, and general practitioners with a special interest in the area, and will have close links with associated surgeons. Practitioners from all these disciplines will have had additional training as well as the core training of their discipline.

Assessment

Typically two and rarely more than three appointments

Establishes a diagnosis

Psychological and endocrine investigation to consider differential diagnoses

Exploration of patients’ social, occupational, psychological, and family circumstances to enable specific, personalised advice on changing gender role

Advice on the medical, legal, and other possibilities (and consequences) for the patient

Management

If indicated, hormone treatment is initiated by clinic (patient needs to be physically fit for treatment)

Speech and communication therapy is offered

Facial hair removal prescribed and funded (in England, not in Wales).

Referral for surgery arranged and funded by clinic:

Bilateral mastectomy with male chest reconstruction

Genital reconstructive surgery

Recommendation for surgery that is arranged and funded by primary care

Hysterectomy

Oophorectomy

The NHS does not fund ear, nose, and throat surgery, augmentation mammoplasty, or facial surgery.

How can non-specialist doctors support other health needs?

Assessment and treatment that are the same

Patients established in a new gender role develop the same medical problems as everyone else. Standard treatment for those conditions is indicated, and the change of gender role need not be a focus.

Assessment and treatment that can differ

Hormone treatment is initiated in a gender identity clinic, but ongoing prescribing will occur in primary care because it is not challenging and will need to be life long. Gender identity clinics can provide support with this ongoing prescribing if required.

Patients who were assigned female at birth and who are living as men might require a hysterectomy and oophorectomies. This, when required, can be undertaken by local gynaecological services. In making or receiving these referrals consider preserving dignity. For example, ask whether patients would prefer to be seen in general surgical rather than gynaecological outpatient clinics. If seen in a gynaecological clinic, patients might feel less conspicuous if accompanied by a woman. Similarly, consider whether ultrasound scans can be performed in general rather than specifically gynaecology imaging departments, and whether the patient might be admitted to a general rather than a gynaecological ward.

Routine screening tools for cardiovascular, respiratory, and bone health are difficult to apply because normative data risk factors are not available for transgender patients. Share this uncertainty about gender related risk factors with the patient, use common sense, and consider the many non-gender related factors that might elevate or reduce their risk of such conditions.

Gender specific screening—be aware that gender reassignment can alter routine recall systems for common cancer screening. Communicate to those setting up recall and processing testing why the sample might appear to come from a person allocated to the opposite sex from that which they might expect.

Consider birth gender when offering routine screening for cervical and breast cancer and aortic aneurysm. For example, women who were assigned male at birth do not need routine mammography. Their risk of breast cancer is very low because there is no progesterone in their hormone treatment (they don’t need it as they have no uterus to protect from unopposed oestrogen induced malignancy). These patients are eligible for aortic aneurysm screening if they have a history of smoking, but will not be called up automatically.

Anybody with a cervix should be offered routine smear tests but the NHS recall system cannot register men. General practitioners can remind patients and alert the cytology services that they have not made a mistake when sending a sample from a man and do require it to be examined.

Complications of gender related surgery

Where possible, problems with both phalloplasty and vaginoplasty might be referred to a urological surgeon with an interest in gender reassignment. A general gynaecological referral for someone who has undergone a vaginoplasty is not appropriate because the patient’s anatomy, unremarkably female as it might look on initial inspection, did not start out as gynaecological and won’t be familiar to most gynaecologists.

Record keeping and communication in the new gender role

Ask patients who change gender role if they want to be registered in their new role and sex and ensure administrative records are changed.5

Greet, seat, and treat the patient in their new role. Ask which pronoun they would prefer to be used and be careful to use it.

Consider suggesting that transgender patients might use whichever lavatory facilities they feel comfortable with, rather than direct them to accessible toilets that they don’t need unless they are disabled. Patients with the active phases of treatment long behind them often live lives indistinguishable from anyone born into their gender role, and disclosures by clinical and administrative staff can be very distressing.

Psychological and peer support

Many larger cities contain active transgender support groups, usually with an online presence. These offer excellent help to patients with problems that arise outside medical care, or with the stress of waiting for a clinic appointment and, later, with the transition process. Counselling services that are run with trans people in mind can be transformational. Investigate if such a service is available locally. Otherwise counselling and support services run for the general population are quite acceptable for trans people in general, but might struggle with trans specific issues.

How this article was made

This article was created using the author’s personal experience together with experience of hearing descriptions of working practice through attendance at national symposiums.

How patients were involved in the creation of this article

EK and NJ were both contributors, EK from the point of view of patient experience, NHS registration changes, and sources of support, and NJ from the point of view of practical primary care challenges and pitfalls.

In response to their comments, we added detail on routine NHS screening and the lack of normative data, and on the likelihood of finding local support groups in urban areas.

Education into practice

Do you know how to change gender assignments on the IT systems at your place of work? Do you know how to make individual exceptions when recalling for standard screening, such as cervical screening or mammography?

Do you know how to refer to your local gender identity clinic or contact them for advice regarding hormone prescriptions?

Do you feel able to ask your patients how they would prefer to be referred to, and do you use gender neutral language if appropriate?

What will you do differently as a result of reading this article?

Additional resources

Transsexual and other disorders of gender identity: a practical guide to management,. Barrett J, ed. Radcliffe Medical Publishing, 2007

Gijs L, Brewaeys A. Surgical treatment of gender dysphoria in adults and adolescents: Recent developments, effectiveness, and challenges. Ann Rev Sex Res 2007;18:178-224.

The Gender Recognition (Disclosure of Information) (England, Wales and Northern Ireland) Order 2005 https://www.health-ni.gov.uk/articles/gender-recognition-disclosure-information-england-wales-and-northern-ireland-no-2-order

McNeil J, Bailey L, Ellis S, Morton J, Regan M. Trans mental health survey 2012. 2012, Edinburgh: Scottish Transgender Alliance.

NHS England. Primary care responsibilities in prescribing and monitoring hormone therapy for transgender and non-binary adults (updated). 2016. https://shsc.nhs.uk/wp-content/uploads/2016/04/SSC1620_GD-Prescribing.pdf

Richards C, Barrett J. The case for bilateral mastectomy and male chest contouring for the female to male transsexual. Ann R Coll Surg Engl 2013;95:93-5.

Footnotes

Contributors: Elizabeth Kasprzyk and Neil Jackson.

EK and NJ contributed on patient view/support groups and as a GP view, respectively. JB is the guarantor.

The authors had no financial interests that were a barrier to authorship in The BMJ. JB is a member of the NHS England Specialised Commissioning Clinical Reference Group on Gender Dysphoria, sat on the Intercollegiate committee that drew up the UK Standards of Care and is the president of the British Association of Gender Identity Specialists.

EK is a patient at a UK gender identity clinic.

NJ has transgender patients on his practice list.

Log in

Log in using your username and password

Log in through your institution

Subscribe from £173 *

Subscribe and get access to all BMJ articles, and much more.

* For online subscription

Access this article for 1 day for:

£38 / $45 / €42 (excludes VAT)

You can download a PDF version for your personal record.